Of the bits of Australian this-and-that that Danny and I did manage to take in, the takeaways reside in the realms of architecture, art, and urban landscapes. (This may not surprise our faithful readers.) These impressions are as fugitive as was our time in the Land Down Under en tout, but there’s no stopping the camera from shooting what it shoots (deliberate cognition plays at best a supporting role), and once images become digitally imprinted, a record of sorts emerges.

Architecture first. Australian cities, or at least Sydney and Melbourne, are organized more like Boston than like New York City, meaning that a relatively small core, usually coincident with the Central Business District, constitutes the eponymous legal municipality, and surrounding it are progressively expanding arcs or rings of suburbs. What differentiates Sydney and Melbourne from Boston is that the size of that inner core is really small, so once you start walking away from the core the suburbs start almost right away. Still, as in Boston, Sydney and Melbourne’s inner suburbs contain older as well as new buildings; spatially, their layout varies, and they bear traces of an orientation toward pedestrians. We’re told that as the distance from the urban core increases, Australian suburbs’ density diminishes, along with the varieties of experience they offer.

The parts of Sydney we walked through to get from Rushcutter’s Bay, the suburb where we stayed, to the downtown harbor area took us through many ranges of tiny, older residential buildings, some in wood,

and others masonry. A few of these areas snuggle up to, or surround a little open area akin to a village green– below, look how some kid just dropped her bicycle and walked in her front door with no thought of locks or bike stands. Just as we all used to do, growing up. Right in the middle of Sydney!

and others masonry. A few of these areas snuggle up to, or surround a little open area akin to a village green– below, look how some kid just dropped her bicycle and walked in her front door with no thought of locks or bike stands. Just as we all used to do, growing up. Right in the middle of Sydney! Nearby stood larger buildings that served the original community — perhaps a library, a school, a church. What the building below was or now is remains a mystery, but it’s fairly typical of the small Victorian public infrastructure in both Sydney and Melbourne.

Nearby stood larger buildings that served the original community — perhaps a library, a school, a church. What the building below was or now is remains a mystery, but it’s fairly typical of the small Victorian public infrastructure in both Sydney and Melbourne.

Then there’s the more majestic stuff. Victorian architects in Australia, it seemed to me, relished their distance from the stodgy old colonial mothership. They seemed to take a good deal of enjoyment in designing over the top– these two building are both in Melbourne, the bottom is the central train station on Flinder’s Street.

Others, of course, contented themselves with Monumental and Sedate. This the former Royal Mail Exchange Building, now the Whitehouse Institute of Design in Melbourne.  That red-brick/yellow-ochre detailing is a common combination in public buildings in both cities.

That red-brick/yellow-ochre detailing is a common combination in public buildings in both cities.

As for more recent buildings, our impression was that the general design quality is higher than in the US — see below, an ordinary luxury residential tower, where the architect at least tried to entertain the eye as it travels, wittingly or not, from base to crest.

Then, there was the special. I’ll wait on a wonderful project by the ever-uneven Jean Nouvel, because it fits best into the urban landscape entry, but here’s a surprising success by the also ever-uneven Frank Gehry, a business school at the University of Technology Sydney.

The canting of the windows on the exterior did just wonderful things with the clouds. (Lucky we caught it on a nice summer day.) And the texture in the brick façade, created by projecting and recessing passages of bricks as they followed the building’s complex curvature, was very successful.

Inside, the building had the same spatial mess of “some cool moves and a lot of afterthoughts” that I’ve come to expect in most Gehry buildings, except the superb Guggenheim Bilbao. Here, the cool move was an element built up of wood blocks that looked as though it fell out of some Brobdingnagian child’s playpen.

The real treat was seeing the Melbourne School of Design, designed Nader Tehrani of NADAAA and John Wardle of John Wardle Architects, which, in the central element-within-atrium motif, may look similar, but I assure you, the resemblance is only superficial. I will write about the masterful MSD elsewhere, so I’ll spare my breath and fingers here. Here are a couple of images, though.

The architects transformed the internal corridors into habitable spaces (see tables and desks at left) and the wire mesh allowed them maintain a degree of visual openness to other floors while abiding by safety regulations.

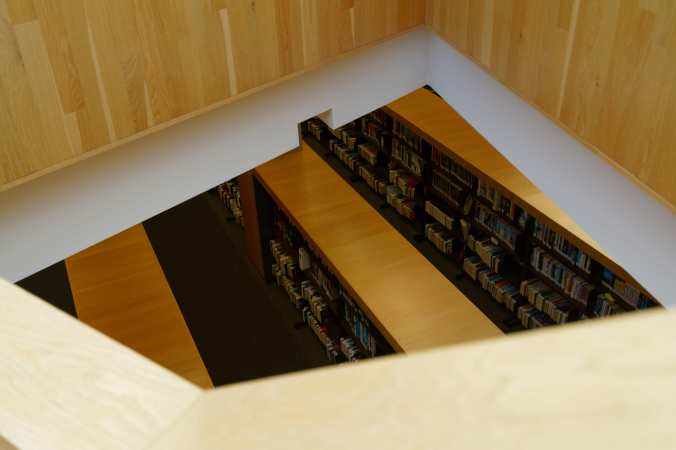

Through that crisscrossing network of family relations that life is, Nader introduced me to John, with whom I spent a good deal of time. One afternoon, Danny and I scoped out a library he did for the Melbourne Grammar School, a tony private school whose original buildings must have been designed with Oxford or Cambridge in mind.

Respectfully, Wardle did something very different, with some beautiful details, inside and out.

Look (below) how the vertical brick headers (are they headers?) project out of the surface as the wall’s plane cants back!

The library’s stacks become an object of curiosity when you get just a peek, from above.

We also saw OMA’s MPavilion 2017 in Queen Victoria Gardens, just because. When you’re passing something branded “Rem Koolhaas”, you stop to poke around a bit– although in this case, not even long enough for a cup of coffee.

Finally, a very nice new building which is the cornerstone of a billion-dollar campus upgrading ongoing at the University of Technology Sydney, by Durbach Block Jaggers, buddies of John Wardle. Appropriately enough, it houses the Graduate School of Health. A ton to say about this one, too, but I’ll just leave you with teasers and eye candy.

— Sarah

New Zealanders, with their seemingly infinite capacity to charm, charmingly call trekking or hiking “tramping”, which constitutes something of a national pastime. Tourist brochures and government-sponsored websites alike advertise the Tongariro Alpine Crossing as the best one-day tramp in the country. Not for the faint of heart, though. It’s 19.4 kilometers (nary a water source along the way), with official estimates advising that hikers to plan on between six and eight hours, with the ominous addendum, “depending upon your condition”. You are also repeatedly reminded to pack for different kinds of weather events: you can shiver in pelting sleet and sweat in blazing rays of sun in a single day. Or you can find yourself at the peak of a dry, sandy, 10-foot-wide ridge huddling against 65 mile-per-hour winds, as happened the

New Zealanders, with their seemingly infinite capacity to charm, charmingly call trekking or hiking “tramping”, which constitutes something of a national pastime. Tourist brochures and government-sponsored websites alike advertise the Tongariro Alpine Crossing as the best one-day tramp in the country. Not for the faint of heart, though. It’s 19.4 kilometers (nary a water source along the way), with official estimates advising that hikers to plan on between six and eight hours, with the ominous addendum, “depending upon your condition”. You are also repeatedly reminded to pack for different kinds of weather events: you can shiver in pelting sleet and sweat in blazing rays of sun in a single day. Or you can find yourself at the peak of a dry, sandy, 10-foot-wide ridge huddling against 65 mile-per-hour winds, as happened the

Circumventing the Red Crater (you couldn’t actually ascend it) brought you into view of the vaginal-looking orifice from which all that lava spewed during its last eruption. From there, you began your multi-houred descent. Around one bend, you see this: the Emerald Lakes (at right). At left-center, in middle distance, you can just glimpse the Blue Lake, and behind it in the horizon, Lake Tapuo, which is a caldera of a different volcano, about 90 miles away.

Circumventing the Red Crater (you couldn’t actually ascend it) brought you into view of the vaginal-looking orifice from which all that lava spewed during its last eruption. From there, you began your multi-houred descent. Around one bend, you see this: the Emerald Lakes (at right). At left-center, in middle distance, you can just glimpse the Blue Lake, and behind it in the horizon, Lake Tapuo, which is a caldera of a different volcano, about 90 miles away.

An army of eateries, several divisions of sleeperies,

An army of eateries, several divisions of sleeperies,

Before pursuing this line, I admit that I recoil a bit from being labeled a tourist, as, whatever its original sense, today it sounds so unserious and connotes at least partly negatively, and I like to buoy my spirits with the mental placebo that what we (Sarah and I, and Sarah, Gideon, and I) should not be clothed in this appellation.

Before pursuing this line, I admit that I recoil a bit from being labeled a tourist, as, whatever its original sense, today it sounds so unserious and connotes at least partly negatively, and I like to buoy my spirits with the mental placebo that what we (Sarah and I, and Sarah, Gideon, and I) should not be clothed in this appellation.

Much of what we do when we visit places relates to our, especially Sarah’s, professional work, and this journey is intended to produce at least a couple of books, so my own perhaps at least partly self-deceptive self-conception as anything but an authenticity-sullying tourist is buttressed and legitimized by our vocational bents and activities. We are at once anthropologists of the globalized world, sociologists of the built and unbuilt environment, social psychologists of family life, and cultural critics of the arts and gluten-free food. Alas, to the untrained eye, we look and sound like tourists. The diagnostic truism “If it looks like a duck, and sounds like a duck…” is either on the money or, like many truisms, not clever enough by half.

Much of what we do when we visit places relates to our, especially Sarah’s, professional work, and this journey is intended to produce at least a couple of books, so my own perhaps at least partly self-deceptive self-conception as anything but an authenticity-sullying tourist is buttressed and legitimized by our vocational bents and activities. We are at once anthropologists of the globalized world, sociologists of the built and unbuilt environment, social psychologists of family life, and cultural critics of the arts and gluten-free food. Alas, to the untrained eye, we look and sound like tourists. The diagnostic truism “If it looks like a duck, and sounds like a duck…” is either on the money or, like many truisms, not clever enough by half. Thus, we call the people at Stowe or Alta “skiers”. The problem with naming the visitors to Queenstown is that we have no linguistic concept that captures what they are, and so we are stuck with choosing between the anodyne “visitors” and the iodine “tourists”.

Thus, we call the people at Stowe or Alta “skiers”. The problem with naming the visitors to Queenstown is that we have no linguistic concept that captures what they are, and so we are stuck with choosing between the anodyne “visitors” and the iodine “tourists”.

In many open areas and public spaces, art installations are carefully installed, including this one, which combines a phone charging area and seating. The public art varies widely in quality, at least it’s there.

In many open areas and public spaces, art installations are carefully installed, including this one, which combines a phone charging area and seating. The public art varies widely in quality, at least it’s there. Not a great building, but an excellent one. (Few projects of any sort, artistic, architectural, or literary, rise to the level of great.) All over Anker Brygge, new, new new:

Not a great building, but an excellent one. (Few projects of any sort, artistic, architectural, or literary, rise to the level of great.) All over Anker Brygge, new, new new:

We had a fine day and previous evening in Oslo, mostly walking and taking in its distinctive urbanity and its fabric, mainly known as buildings.

We had a fine day and previous evening in Oslo, mostly walking and taking in its distinctive urbanity and its fabric, mainly known as buildings.

In the early afternoon, just as it was beginning to rain, we visited and marveled at Snohetta’s renowned Opera House.

In the early afternoon, just as it was beginning to rain, we visited and marveled at Snohetta’s renowned Opera House.

Sarah and I set out on our adventure with the purpose of writing books, one by her and one by me, very different in character, each possible only through this long journey. More on them in a moment. We also set out committed to the writerly experiment of this let-the-spirit-move-us collaborative blog, which includes Gideon, who, I hope, will make his entry here soon and thereafter frequently. For Sarah and for me (about Gideon, who also has other writing projects, I’m not sure), the question of what goes where is live, and, at least for me, has not been resolved clearly.

Sarah and I set out on our adventure with the purpose of writing books, one by her and one by me, very different in character, each possible only through this long journey. More on them in a moment. We also set out committed to the writerly experiment of this let-the-spirit-move-us collaborative blog, which includes Gideon, who, I hope, will make his entry here soon and thereafter frequently. For Sarah and for me (about Gideon, who also has other writing projects, I’m not sure), the question of what goes where is live, and, at least for me, has not been resolved clearly.  Roughly speaking, my schema is to offer you accounts and observations about the world out there which we encounter on our carefully chosen itinerary of barely scratching the world’s surface, even with a year of scratching at our disposal. The inner workings and inter-workings of the three of us – what it is like to travel with two loved ones for a year, and how the many and ongoing encounters with one another and with the offerings and demands of the world we will wend our way through affect and change us as individuals and in our relationships as parents and child, as married people, as individuals positioned differently in the ever-changing arrays of living – these things about us are the stuff and soul of the book. The rub might be obvious: the line, actually lines demarcating what’s out there from what’s in here (the family circle and each of our minds and hearts) is hard to draw, especially as the inside is implicated in the outside, most essentially because both constitute and are filtered through experience, thought, and language. (Taking and posting photos – Sarah’s and Gideon’s domains – are more clear cut.) So, deciding what’s in and out of the blog, because what constitutes the in(side) and the out(side) of the respective worlds we are living and seeking to understand is often indeterminate, is an ongoing and inherently messy and probably shifting process which I am negotiating with that very tough and a bit ambivalent negotiator, myself. As to the other negotiator involved here, I think less beset by this manner of thinking, I’ll leave it to her to engage her blog/book issues herself.

Roughly speaking, my schema is to offer you accounts and observations about the world out there which we encounter on our carefully chosen itinerary of barely scratching the world’s surface, even with a year of scratching at our disposal. The inner workings and inter-workings of the three of us – what it is like to travel with two loved ones for a year, and how the many and ongoing encounters with one another and with the offerings and demands of the world we will wend our way through affect and change us as individuals and in our relationships as parents and child, as married people, as individuals positioned differently in the ever-changing arrays of living – these things about us are the stuff and soul of the book. The rub might be obvious: the line, actually lines demarcating what’s out there from what’s in here (the family circle and each of our minds and hearts) is hard to draw, especially as the inside is implicated in the outside, most essentially because both constitute and are filtered through experience, thought, and language. (Taking and posting photos – Sarah’s and Gideon’s domains – are more clear cut.) So, deciding what’s in and out of the blog, because what constitutes the in(side) and the out(side) of the respective worlds we are living and seeking to understand is often indeterminate, is an ongoing and inherently messy and probably shifting process which I am negotiating with that very tough and a bit ambivalent negotiator, myself. As to the other negotiator involved here, I think less beset by this manner of thinking, I’ll leave it to her to engage her blog/book issues herself. Lofoton, above the Arctic Circle in midnight summertime sun Norway, was a spectacular place to begin our journey. The breath-taking and -giving monumental landscapes, which can be imaginatively discerned well enough through the miniaturized photos (which I expect Sarah will happily insert), as a undulating symphony of approachable mountains and hills, and lakes and fjords. We drove for hours through it at nearly every hour of the 24-hour day, including 1 in the morning, 5 in the morning, 9 in the evening, 11 in the evening and the more conventional sightseeing times in-between. Riveted and scanning, still and pointing, quiet and in full conversation (see shadows above), we drove, we walked, we looked, we breathed, we experienced Lofoton. For two days our ordinary rhythms of sleeping and waking, eating and… we cast asunder. We walked (see Gideon, double above), we hiked (straight up a small mountain nearing midnight), we drank coffee outdoors in the just warm enough weather, as we lived according to our own time- and activity-wants. We valiantly twice tried to see the sun at solar midnight descend, bounce, and rise slightly above the horizon, and failed for differently reasons. The attempts felt (in our exaggerating subjectivity) near-heroic, so we, the reasonable agents we are, felt disappointed yet satisfied that we had done our best. And so, we have yet another reason to return to Lofoton, to find and follow the midnight sun.

Lofoton, above the Arctic Circle in midnight summertime sun Norway, was a spectacular place to begin our journey. The breath-taking and -giving monumental landscapes, which can be imaginatively discerned well enough through the miniaturized photos (which I expect Sarah will happily insert), as a undulating symphony of approachable mountains and hills, and lakes and fjords. We drove for hours through it at nearly every hour of the 24-hour day, including 1 in the morning, 5 in the morning, 9 in the evening, 11 in the evening and the more conventional sightseeing times in-between. Riveted and scanning, still and pointing, quiet and in full conversation (see shadows above), we drove, we walked, we looked, we breathed, we experienced Lofoton. For two days our ordinary rhythms of sleeping and waking, eating and… we cast asunder. We walked (see Gideon, double above), we hiked (straight up a small mountain nearing midnight), we drank coffee outdoors in the just warm enough weather, as we lived according to our own time- and activity-wants. We valiantly twice tried to see the sun at solar midnight descend, bounce, and rise slightly above the horizon, and failed for differently reasons. The attempts felt (in our exaggerating subjectivity) near-heroic, so we, the reasonable agents we are, felt disappointed yet satisfied that we had done our best. And so, we have yet another reason to return to Lofoton, to find and follow the midnight sun.