So, a little mop-up in the guise of a recap is left to somewhat compositionally-AWOL me.

We began in Queenstown, which is charming, offering a well-conceived and articulated built environment as the human crown jewel set within, or the comparatively inevitably impoverished jumping-off point into, the spectacular and varied landscapes dominated and structured by the inestimably beautiful Southern Alps.  To give Queenstown its due, it is perhaps the most beautiful and monumental setting of any urban area (it’s a small one) we have seen.

To give Queenstown its due, it is perhaps the most beautiful and monumental setting of any urban area (it’s a small one) we have seen.

Typical street scene in Queenstown (republished)

The town offers a hubbub of activity, as it is animated by its narrow streets and pathways, its small-scale and muscular urban and building design, and its energetic, on-the-go, hiker-accentuated human aesthetic. To use the indistinct (not my favorite way) but evocative (that’s good) phrases: The place and the people are happening, have good energy, give off a good vibe.

The vibe in Queenstown: there were dozens of these on the hike up Queenstown Hill

The landscapes of the region we have justly gushed (never enough) about. Even the humdrum among them – the city park, and an elevation-static walk starting in Queenstown along the lake and then beyond – are memorable and prospectively never tiring. Our one disappointment, not being able to walk/hike the three-day Routeburn Track, reputably among the most exquisite in New Zealand, owing to a minor injury Gideon sustained, turned into a compensatory boon of us getting to explore by car and foot more of the Queenstown region. After leaving the urban and in its own way urbane area of Queenstown, we drove through the seductive temperate rainforest

The landscapes of the region we have justly gushed (never enough) about. Even the humdrum among them – the city park, and an elevation-static walk starting in Queenstown along the lake and then beyond – are memorable and prospectively never tiring. Our one disappointment, not being able to walk/hike the three-day Routeburn Track, reputably among the most exquisite in New Zealand, owing to a minor injury Gideon sustained, turned into a compensatory boon of us getting to explore by car and foot more of the Queenstown region. After leaving the urban and in its own way urbane area of Queenstown, we drove through the seductive temperate rainforest

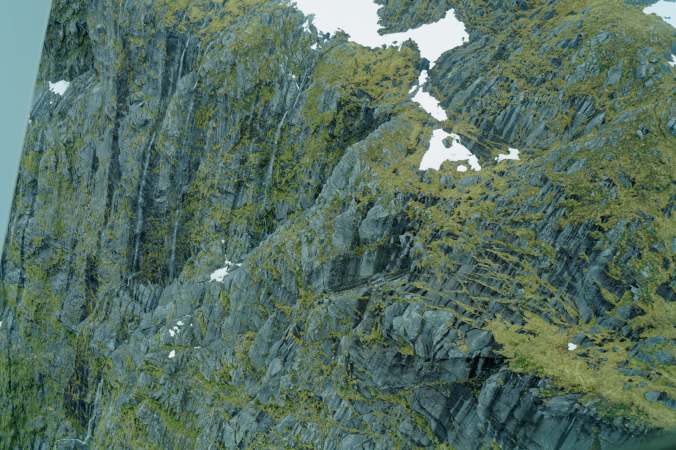

Nature’s extravagance: a roadside embankment on the West Coast

– it was, mostly on and sometimes off, wet with rain –  and mountainscapes of the west coast, fittingly named West Coast, and then across the mountain isthmus of Arthur’s Pass to a more conventional and more distinctive urban experience of Christchurch.

and mountainscapes of the west coast, fittingly named West Coast, and then across the mountain isthmus of Arthur’s Pass to a more conventional and more distinctive urban experience of Christchurch.

In composing our journey, we usually seek to alternate types of places, so as to maximize contrasts — which constrains that assassin of experience, habituation — and the wonder of novelty. Though there are several of these types of alternations, the most obvious and frequently employed is the rural-urban one, which also often can be characterized by hiking trails vs. walking pavement and urban parks, and what each respectively brings us to.

Botanic Gardens, Christchurch (“the Green City”), with Sarah’s favorite flowers: irises

So, we ended our rural bacchanalia of the South Island with a few days in Christchurch, its largest city, the third largest in New Zealand.

Old Government Building (1912), now a Heritage Hotel, Christchurch

Even though I have nothing to add to Sarah’s magnificent portrait of reemerging Christchurch, I will mention a humdrum item – although many such items exist on the trip, but a nonprecious few make it into its official portrayal here. We discovered Macpac, a New Zealand analogue of Patagonia. When we were preparing for this trip, having resolved to bear gear and clothing of low volume and weight (essentially what hikers tote), which means hi-tech polyester, I of sensitive skin found only one line of shirts (from Patagonia) I could withstand. I got six of them for the trip.

One problem: Sarah hates their appearance. She says, because they are objectively hideous. In a willing bow to her, I have checked out a generous helping of outdoors stores, including those we happen upon, without success. Enter Macpac, which had a shirt of all the magical qualities — light, low volume, wicking — which I could epidermally tolerate, was more conventional material-like in feel and look, and which Sarah (and Gideon) liked.

Instant wardrobe replacement of short- and long-sleeve shirts, transforming me from a daily advertisement for Patagonia into one for Macpac.

Needing to fly somewhere in the North Island to resume our urban-rural alternation, we decided on the small Art Deco city extraordinaire Napier,

Napier, on the North Island, has a Miami vibe

where we strolled for a few hours thinking of an architecturally unsullied Miami Beach and disputating the desirability of returning to Napier someday for a longer stint, before heading off by car to Tongariro, and its justly famous transalpine tramp. After four days of our rural and hiking wonders of Tongariro

where we strolled for a few hours thinking of an architecturally unsullied Miami Beach and disputating the desirability of returning to Napier someday for a longer stint, before heading off by car to Tongariro, and its justly famous transalpine tramp. After four days of our rural and hiking wonders of Tongariro  (Sarah: “I would do that hike every year”) and Rotorua – both of Hobbit/Lord of the Rings fame – we finished off our New Zealand romp with two solid days in Auckland’s Viaduct area, with a splendid view of the harbor, urbanity, and enough worthy activities to keep us happy.

(Sarah: “I would do that hike every year”) and Rotorua – both of Hobbit/Lord of the Rings fame – we finished off our New Zealand romp with two solid days in Auckland’s Viaduct area, with a splendid view of the harbor, urbanity, and enough worthy activities to keep us happy.

Waterfront and Historic Ferry Building (1912) in downtown Auckland

Gideon went off on his own to do his solo-city-thing, this time to the concussive detriment of his head. Sarah and I went off to do our art and architecture thing, most notably at the lovely Auckland Art Gallery,

New wing, Auckland Art Gallery, FJMT and Archimedia (2011)

Old Wing, Auckland Art Gallery (1888, originally the Auckland Public Library)

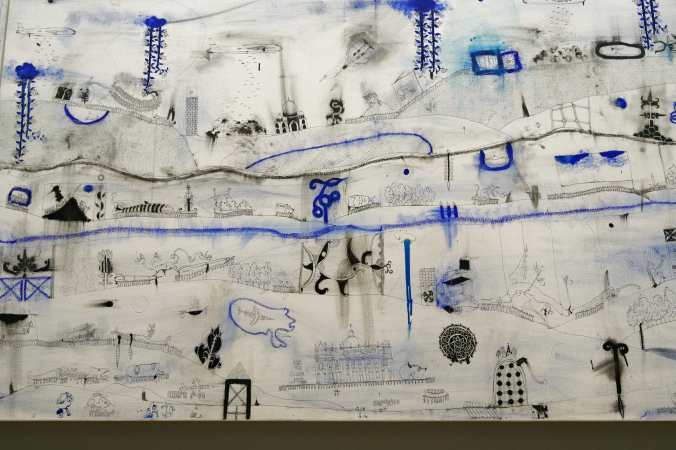

John Pule, Kehe Tau Hauaga Foou “To All New Arrivals” (2007), detail, Auckland Art Gallery (note façade of St. Peters, center bottom, and Taj Mahal, center top)

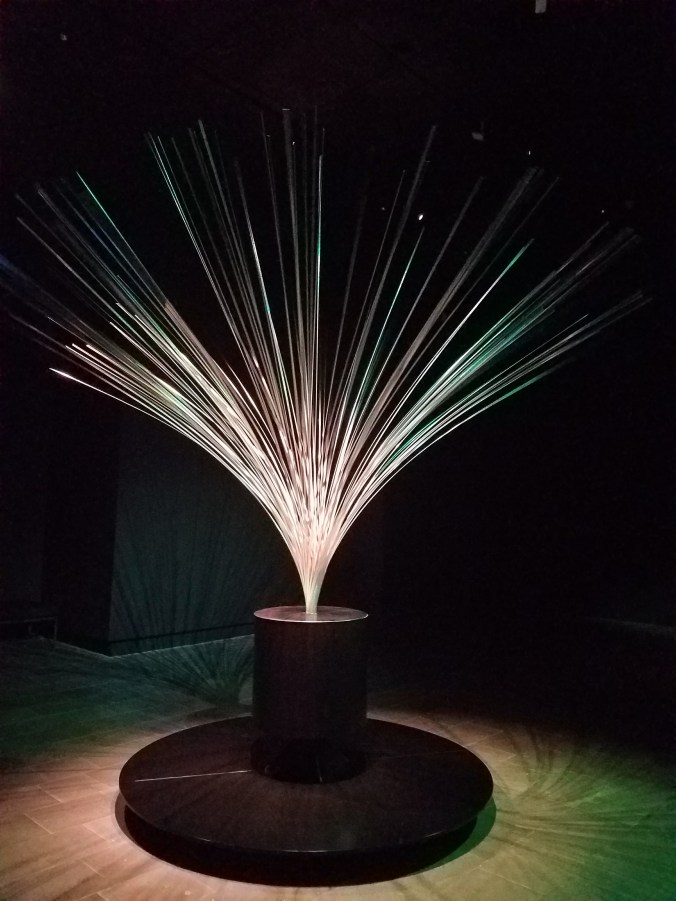

having already in the Christchurch Art Gallery seen a wonderful Bridget Reilly show and discovered a fabulous kinetic artist, Len Lye,

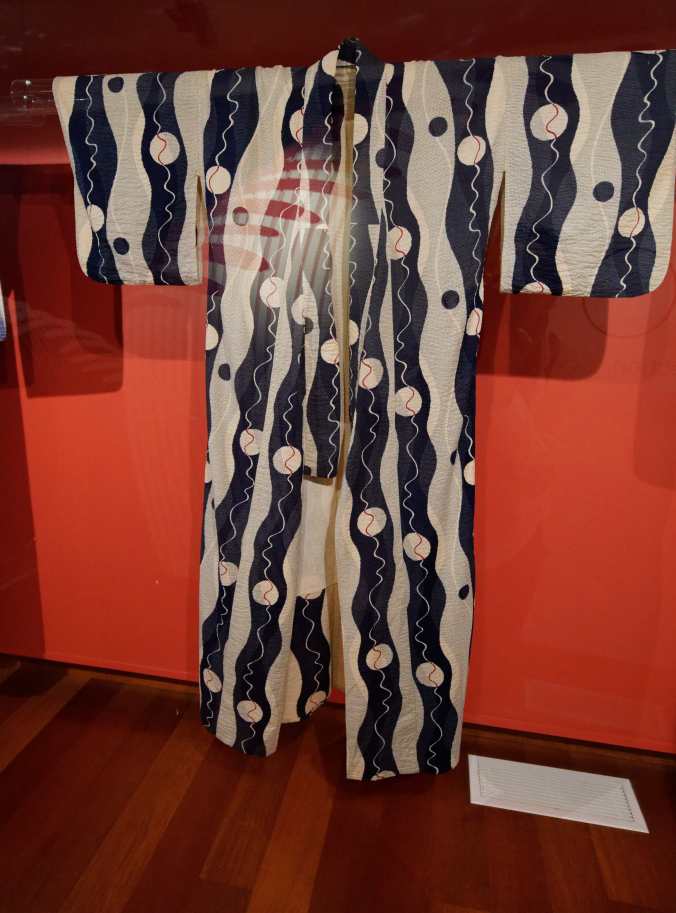

and in the a Napier museum, receiving the unexpected pleasure of being introduced to a merging of arts we had not imagined in the body (really body-covers) of historic Art Deco Kimonos!

and in the a Napier museum, receiving the unexpected pleasure of being introduced to a merging of arts we had not imagined in the body (really body-covers) of historic Art Deco Kimonos!

In sum, in New Zealand we drove ourselves South to North and then again South to North  immersing ourselves in the experience of the most magnificent landscapes of nature’s pacific and tumultuous offerings, getting a taste or more of the largest (Auckland, 1.5M), third largest (Christchurch, 400K), sixth largest (Napier, 130K), tenth largest (Rotorua, 60K), and barely-large-enough-to-be-one, placing 27th (Queenstown, 15K) city, and many larger and smaller towns in-between, and taking pleasure in some of the finer products of human creativity. Everywhere and without exception, the New Zealanders were friendly, helpful, informed, and well-spoken in, at least to me, their charmingly accented English. They appear to know that they have something extraordinary going for them,

immersing ourselves in the experience of the most magnificent landscapes of nature’s pacific and tumultuous offerings, getting a taste or more of the largest (Auckland, 1.5M), third largest (Christchurch, 400K), sixth largest (Napier, 130K), tenth largest (Rotorua, 60K), and barely-large-enough-to-be-one, placing 27th (Queenstown, 15K) city, and many larger and smaller towns in-between, and taking pleasure in some of the finer products of human creativity. Everywhere and without exception, the New Zealanders were friendly, helpful, informed, and well-spoken in, at least to me, their charmingly accented English. They appear to know that they have something extraordinary going for them,  and, generous lot that they are — here’s a woman who runs a weekly open-air soup kitchen in Auckland, offering us a meal —

and, generous lot that they are — here’s a woman who runs a weekly open-air soup kitchen in Auckland, offering us a meal —  they don’t mind sharing the natural and urbanistic wealth.

they don’t mind sharing the natural and urbanistic wealth.

We were, and left, and shall return, the richer for it.

— Danny

One place that succeeded in earning a top spot in our greatest hits album (maybe that’s this blog) was in the volcanic Rotorua region, which includes the Tarewera, a volcano that has erupted 5 times in last 18,000 years (one so extreme that it cast volcanic dust as far away as Greenland), as well as the Waimangu. The last major eruption of the volcanic craters all along Waimangu valley was in 1886, which falls easily within the era of photography. The

One place that succeeded in earning a top spot in our greatest hits album (maybe that’s this blog) was in the volcanic Rotorua region, which includes the Tarewera, a volcano that has erupted 5 times in last 18,000 years (one so extreme that it cast volcanic dust as far away as Greenland), as well as the Waimangu. The last major eruption of the volcanic craters all along Waimangu valley was in 1886, which falls easily within the era of photography. The  The Waimangu regaled us with hot waters,

The Waimangu regaled us with hot waters, and hot (and cool, in both senses of the word) colors,

and hot (and cool, in both senses of the word) colors,

and with a tiny, even cute little geyser (below, at the left side of the image), wholly unlike the more conventional tower of water we saw a few years ago outside of Reykjavik in the gushing font that gave its name to this natural though relatively rare phenomenon, Geysir.

and with a tiny, even cute little geyser (below, at the left side of the image), wholly unlike the more conventional tower of water we saw a few years ago outside of Reykjavik in the gushing font that gave its name to this natural though relatively rare phenomenon, Geysir.

that reminded Sarah of one of her newish-ly favorite paintings, by Gustav Klimt, which we saw in an exhibition of landscape art from The Paul G. Allen Family Collection at the Phillips Collection in Washington DC.

that reminded Sarah of one of her newish-ly favorite paintings, by Gustav Klimt, which we saw in an exhibition of landscape art from The Paul G. Allen Family Collection at the Phillips Collection in Washington DC.

offering a skylet-high tree walkway,

offering a skylet-high tree walkway,  right outside the city of Rotorua, the forest the result of a tree growing commercial experiment which brought the trees over from California way-back-when-enough that the (skinny) redwoods reach (from unverified memory) three hundred feet and more.

right outside the city of Rotorua, the forest the result of a tree growing commercial experiment which brought the trees over from California way-back-when-enough that the (skinny) redwoods reach (from unverified memory) three hundred feet and more.

make Maya Lin’s land-sculpture in Storm King Sculpture Park,

make Maya Lin’s land-sculpture in Storm King Sculpture Park, which we once admired, a bit self-mocking. Driving through hours of such hillocks made for the greenest mad-undulating landscape this side of our known experience.

which we once admired, a bit self-mocking. Driving through hours of such hillocks made for the greenest mad-undulating landscape this side of our known experience. Sarah’s favorite tree — its name escapes us — was that black-barked fern, plentiful in much of New Zealand, which, in rain-forest-y

Sarah’s favorite tree — its name escapes us — was that black-barked fern, plentiful in much of New Zealand, which, in rain-forest-y  New Zealanders, with their seemingly infinite capacity to charm, charmingly call trekking or hiking “tramping”, which constitutes something of a national pastime. Tourist brochures and government-sponsored websites alike advertise the Tongariro Alpine Crossing as the best one-day tramp in the country. Not for the faint of heart, though. It’s 19.4 kilometers (nary a water source along the way), with official estimates advising that hikers to plan on between six and eight hours, with the ominous addendum, “depending upon your condition”. You are also repeatedly reminded to pack for different kinds of weather events: you can shiver in pelting sleet and sweat in blazing rays of sun in a single day. Or you can find yourself at the peak of a dry, sandy, 10-foot-wide ridge huddling against 65 mile-per-hour winds, as happened the

New Zealanders, with their seemingly infinite capacity to charm, charmingly call trekking or hiking “tramping”, which constitutes something of a national pastime. Tourist brochures and government-sponsored websites alike advertise the Tongariro Alpine Crossing as the best one-day tramp in the country. Not for the faint of heart, though. It’s 19.4 kilometers (nary a water source along the way), with official estimates advising that hikers to plan on between six and eight hours, with the ominous addendum, “depending upon your condition”. You are also repeatedly reminded to pack for different kinds of weather events: you can shiver in pelting sleet and sweat in blazing rays of sun in a single day. Or you can find yourself at the peak of a dry, sandy, 10-foot-wide ridge huddling against 65 mile-per-hour winds, as happened the

Circumventing the Red Crater (you couldn’t actually ascend it) brought you into view of the vaginal-looking orifice from which all that lava spewed during its last eruption. From there, you began your multi-houred descent. Around one bend, you see this: the Emerald Lakes (at right). At left-center, in middle distance, you can just glimpse the Blue Lake, and behind it in the horizon, Lake Tapuo, which is a caldera of a different volcano, about 90 miles away.

Circumventing the Red Crater (you couldn’t actually ascend it) brought you into view of the vaginal-looking orifice from which all that lava spewed during its last eruption. From there, you began your multi-houred descent. Around one bend, you see this: the Emerald Lakes (at right). At left-center, in middle distance, you can just glimpse the Blue Lake, and behind it in the horizon, Lake Tapuo, which is a caldera of a different volcano, about 90 miles away.

The Maori people were never very numerous on these islands; currently, they account for three per cent of the country’s population. Such gestures go part way to redress past wrongs to these indigenous people, to be sure, but I suspect it and all these other historical markers serve a larger function: that of constructing a robust narrative of NZ nationhood and identity.

The Maori people were never very numerous on these islands; currently, they account for three per cent of the country’s population. Such gestures go part way to redress past wrongs to these indigenous people, to be sure, but I suspect it and all these other historical markers serve a larger function: that of constructing a robust narrative of NZ nationhood and identity.

which creates a subtle, compelling dynamism in the nave,

which creates a subtle, compelling dynamism in the nave,

Building has proceeded slowly in the Central Business District — Christchurchians grumble about it, then shrug, adding, it’s a great city. The CBD has been divided into precincts for retail, “innovation” (which I gather means hi-tech), health, performing and visual arts, and “justice and emergency services”. Dozens of large new buildings are under construction: a new metro sports facility, a new central library, a new convention center. A new transit and bus station opened recently.

Building has proceeded slowly in the Central Business District — Christchurchians grumble about it, then shrug, adding, it’s a great city. The CBD has been divided into precincts for retail, “innovation” (which I gather means hi-tech), health, performing and visual arts, and “justice and emergency services”. Dozens of large new buildings are under construction: a new metro sports facility, a new central library, a new convention center. A new transit and bus station opened recently.

A couple of days of walking around the city suggested that the Little Black Hut’s design finesse was not unusual: most homes are small, but the detailing and compositional sensibility even in little cinder block, wood, or corrugated-metal-sided homes looks pretty well done.

A couple of days of walking around the city suggested that the Little Black Hut’s design finesse was not unusual: most homes are small, but the detailing and compositional sensibility even in little cinder block, wood, or corrugated-metal-sided homes looks pretty well done.

How little we missed the “sense of history” so prized amongst Americans! Running into the few remaining Victorian houses, grand and modest, provided enjoyment but not the sense of relief one finds when stumbling upon even modest historic structures in the United States. What we found in Christchurch substantiates the argument I advanced in WtYW that the problem in the US built environment is less old (better)-versus-new (clueless), but the poor design quality and craftsmanship of new construction. In Christchurch, high quality new homes, commercial, and retail buildings could be found everywhere. Even the mediocre buildings are good.

How little we missed the “sense of history” so prized amongst Americans! Running into the few remaining Victorian houses, grand and modest, provided enjoyment but not the sense of relief one finds when stumbling upon even modest historic structures in the United States. What we found in Christchurch substantiates the argument I advanced in WtYW that the problem in the US built environment is less old (better)-versus-new (clueless), but the poor design quality and craftsmanship of new construction. In Christchurch, high quality new homes, commercial, and retail buildings could be found everywhere. Even the mediocre buildings are good.  Stay tuned, then, for the new iteration of New Zealand’s garden city — and dream.

Stay tuned, then, for the new iteration of New Zealand’s garden city — and dream.

and here’s the sunrise that greeted us in the morning.

and here’s the sunrise that greeted us in the morning.

seeing those mountains shooting straight out of its deep, black waters is unforgettable.

seeing those mountains shooting straight out of its deep, black waters is unforgettable.

An army of eateries, several divisions of sleeperies,

An army of eateries, several divisions of sleeperies,

Before pursuing this line, I admit that I recoil a bit from being labeled a tourist, as, whatever its original sense, today it sounds so unserious and connotes at least partly negatively, and I like to buoy my spirits with the mental placebo that what we (Sarah and I, and Sarah, Gideon, and I) should not be clothed in this appellation.

Before pursuing this line, I admit that I recoil a bit from being labeled a tourist, as, whatever its original sense, today it sounds so unserious and connotes at least partly negatively, and I like to buoy my spirits with the mental placebo that what we (Sarah and I, and Sarah, Gideon, and I) should not be clothed in this appellation.

Much of what we do when we visit places relates to our, especially Sarah’s, professional work, and this journey is intended to produce at least a couple of books, so my own perhaps at least partly self-deceptive self-conception as anything but an authenticity-sullying tourist is buttressed and legitimized by our vocational bents and activities. We are at once anthropologists of the globalized world, sociologists of the built and unbuilt environment, social psychologists of family life, and cultural critics of the arts and gluten-free food. Alas, to the untrained eye, we look and sound like tourists. The diagnostic truism “If it looks like a duck, and sounds like a duck…” is either on the money or, like many truisms, not clever enough by half.

Much of what we do when we visit places relates to our, especially Sarah’s, professional work, and this journey is intended to produce at least a couple of books, so my own perhaps at least partly self-deceptive self-conception as anything but an authenticity-sullying tourist is buttressed and legitimized by our vocational bents and activities. We are at once anthropologists of the globalized world, sociologists of the built and unbuilt environment, social psychologists of family life, and cultural critics of the arts and gluten-free food. Alas, to the untrained eye, we look and sound like tourists. The diagnostic truism “If it looks like a duck, and sounds like a duck…” is either on the money or, like many truisms, not clever enough by half.