MOST people probably know many things about the Land Down Under, but if it happens that it’s only one or two things, likely these include the tale of how, when the British began colonizing Australia’s eastern shores in the late 1800s, boatloads of jailbirds were involuntarily hauled in tow. Prison wards in England were crammed full, dark and tight (just read Dickens’ Little Dorrit); offloading convicts to the colonies was one way to relieve overcrowding. Many of those forcibly resettled unfortunates had been found guilty only of minor crimes — forging checks, unpaid debts, that sort of thing. Others had committed worse. Either way, once they’d served out their sentences, many stayed.

Old Melbourne Gaol, 1838-1845

From this single, oft-tapped historical spigot of a fact, a fountain of cultural stereotypes continues to gush. Such as: Australian bodies, especially male bodies, come blonde, big-boned, and saturated with unusually high alcohol content. Australian social practices tend toward the big-hearted and ever-so-slightly crass. Australians incline toward the provincial; inward-looking, they can be a bit quizzical if not suspicious about the pertinence to them and theirs of knowledge harking from beyond their continent’s shores.

Time to shut that spigot off for good. It’s all nonsense. (Indeed so much so that I predict that Danny will object to my writing the paragraphs above, maintaining that one shouldn’t risk perpetuating untruths by recyling them, even if only to discount their veracity.) Since 1996, year after year, the largest percentage of immigrants settling here hail from South and East Asia (you can see the statistics here: http://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about/reports-publications/research-statistics/statistics/live-in-australia/historical-migration-statistics). And though it’s true that around 20% of Australians claim a convict in their ancestry, that means 80% don’t — and one distant convict in one’s otherwise full ancestral tree is hardly a mark of Cain. Besides, what does it matter? The last flotilla of villainy landed here in 1868, 160 years and many generations ago.

Nonetheless, architectural artifacts of the country’s penal heritage constitute its earliest landmarks. Some, as in Sydney, are buried beneath later infrastructure near the shoreline (near the Barangaroo Reserve in Sydney, below); others, like the splendid, if forbidding Old Melbourne Gaol (above), are historic monuments.

Barangaroo Reserve, Sydney

Today, these are but tiny, obdurate reminders of Australia’s early history, buried in the urban fabric of its cities. So what can we say, even provisionally, about Australian urbanism given our scant exposure to Sydney and Melbourne?

Sydney and Melbourne’s sites differ, for sure. Hilly Sydney boasts of its fun-in-the-sun, 150 decadent miles of shoreline, and that’s not even counting ever-hungrily-land-sucking suburbs. Melbourne’s largely undifferentiated flatlands are slung lazily along the muddy, unprepossessing Yarra River. Even so, their patterns of urban development and growth vary less, or so it seemed to me. And if Sydney and Melbourne’s urbanism represents any sort of larger reality (I wager they do), then Australians have by and large embraced, and more or less consistently practiced admirable social democratic ideals: what we saw evinced a well-considered, well-constructed, well-ordered civil society, even with predictable infelicities of all sorts notwithstanding. We saw this in the residential areas and in the city’s newer public spaces, the topic of the next post.

WE situated ourselves in the so-called “inner ring” suburbs, which seems to denote a distance from the urban core of approximately 4-5 kilometers. Our first stop in Melbourne was tiny Middle Park (population ca. 4000), conveniently proximate both to the City Center and the Pacific Ocean. The neighborhood retains an impressive stock of diminuitive Victorian residences (many with ornate cast iron porch details, as below), most in reasonably good repair.

Scattered around, tucked between the older homes, are a number of modern single-family dwellings. It’s one of the better ones of these newer places that we managed to score. Tiny: two bedrooms upstairs; kitchen, living and dining room down. A nice patio in back, though.

The recessed light well, at right, broke up the linearity of the main living area and admitted all manner of light and weather, including the torrential rains with which we were greeted –four seasons in a day, Uber drivers told us again and again, pontificating about the city’s fickle weather. Anyway, our little Middle Park abode proved a hospitable place to enjoy even the downpours, presenting them artfully, at a slight remove.

The recessed light well, at right, broke up the linearity of the main living area and admitted all manner of light and weather, including the torrential rains with which we were greeted –four seasons in a day, Uber drivers told us again and again, pontificating about the city’s fickle weather. Anyway, our little Middle Park abode proved a hospitable place to enjoy even the downpours, presenting them artfully, at a slight remove.

Itinerants we are, ever subject to the booking impulses of Airbnb’ers the world over as well as our own changing needs, we had to move after a fistful of days. We landed in a that-much-smaller place, an apartment in a residential high-rise in South Yarra, a decidedly more upscale, far denser district (population ca. 25,000), although its distance from the city center equivalent to that of Middle Park. From there, we got to survey Melbourne’s horizontal and vertical spread.

Scattered hillocks of towers, residential and commercial, pop up from the lilyponds of two-to-four story mixed-use buildings which spread in nearly every direction, all the way to the horizon.

Scattered hillocks of towers, residential and commercial, pop up from the lilyponds of two-to-four story mixed-use buildings which spread in nearly every direction, all the way to the horizon. In commerical and higher-density residential neighborhoods, the taller structures indicate that Melbourne, like Sydney, takes its towers seriously.

In commerical and higher-density residential neighborhoods, the taller structures indicate that Melbourne, like Sydney, takes its towers seriously.

New ones, and old ones, too.

In any case, in both cities, it seems that they’re erecting a lot more of them.  I tried to discover statistics on new residential and office space real estate, but curiosity vanished in the deluge of Google hits beckoning me to bankers’ and developers’ websites, so I’ll just go with the information offered by Meaghan Dwyer of John Wardle Architects: in both cities, there’s a lot of building going on.

I tried to discover statistics on new residential and office space real estate, but curiosity vanished in the deluge of Google hits beckoning me to bankers’ and developers’ websites, so I’ll just go with the information offered by Meaghan Dwyer of John Wardle Architects: in both cities, there’s a lot of building going on.

Much of it good, and good in ways that indicate a heartening — or shall I say big-hearted?– vision of a social realm that supports sociability for all city-dwellers, not just the wildly privileged.

For notable public spaces and landscapes in both cities and what they might mean, stay tuned.

— Sarah

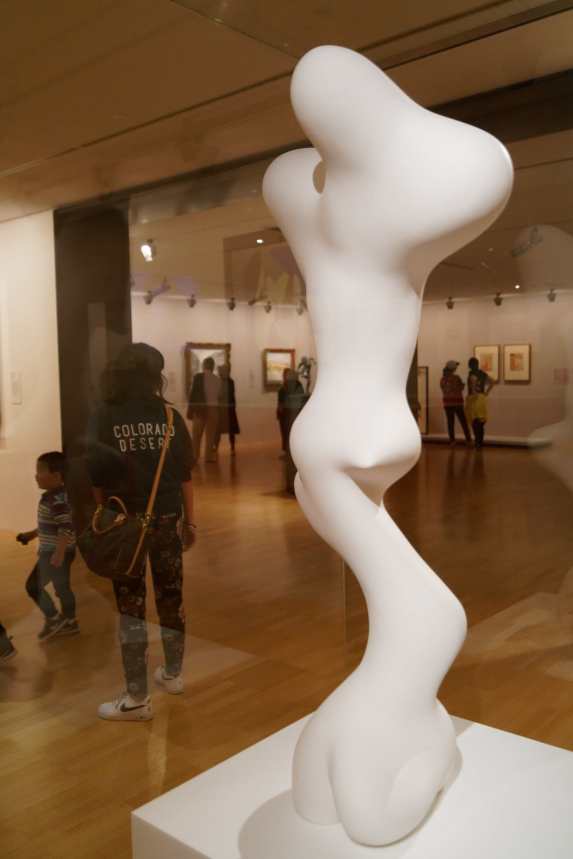

Then we practically ran straight into one of the best Hans (aka Jean) Arp sculptures, from his “Growth” series, that I’ve ever encountered. I was really tempted to hug it.

Then we practically ran straight into one of the best Hans (aka Jean) Arp sculptures, from his “Growth” series, that I’ve ever encountered. I was really tempted to hug it.

Since mirrors can be used to visually diminish the scale of the object they reflect, you get to experience the piece both as it envelops you, spreading majestically over your head and bleeding into your peripheral vision, and at the same time, regard its entirety by glancing toward the silvery pools of light near your feet.

Since mirrors can be used to visually diminish the scale of the object they reflect, you get to experience the piece both as it envelops you, spreading majestically over your head and bleeding into your peripheral vision, and at the same time, regard its entirety by glancing toward the silvery pools of light near your feet.

and others masonry. A few of these areas snuggle up to, or surround a little open area akin to a village green– below, look how some kid just dropped her bicycle and walked in her front door with no thought of locks or bike stands. Just as we all used to do, growing up. Right in the middle of Sydney!

and others masonry. A few of these areas snuggle up to, or surround a little open area akin to a village green– below, look how some kid just dropped her bicycle and walked in her front door with no thought of locks or bike stands. Just as we all used to do, growing up. Right in the middle of Sydney! Nearby stood larger buildings that served the original community — perhaps a library, a school, a church. What the building below was or now is remains a mystery, but it’s fairly typical of the small Victorian public infrastructure in both Sydney and Melbourne.

Nearby stood larger buildings that served the original community — perhaps a library, a school, a church. What the building below was or now is remains a mystery, but it’s fairly typical of the small Victorian public infrastructure in both Sydney and Melbourne.

That red-brick/yellow-ochre detailing is a common combination in public buildings in both cities.

That red-brick/yellow-ochre detailing is a common combination in public buildings in both cities.

The Maori people were never very numerous on these islands; currently, they account for three per cent of the country’s population. Such gestures go part way to redress past wrongs to these indigenous people, to be sure, but I suspect it and all these other historical markers serve a larger function: that of constructing a robust narrative of NZ nationhood and identity.

The Maori people were never very numerous on these islands; currently, they account for three per cent of the country’s population. Such gestures go part way to redress past wrongs to these indigenous people, to be sure, but I suspect it and all these other historical markers serve a larger function: that of constructing a robust narrative of NZ nationhood and identity.

which creates a subtle, compelling dynamism in the nave,

which creates a subtle, compelling dynamism in the nave,

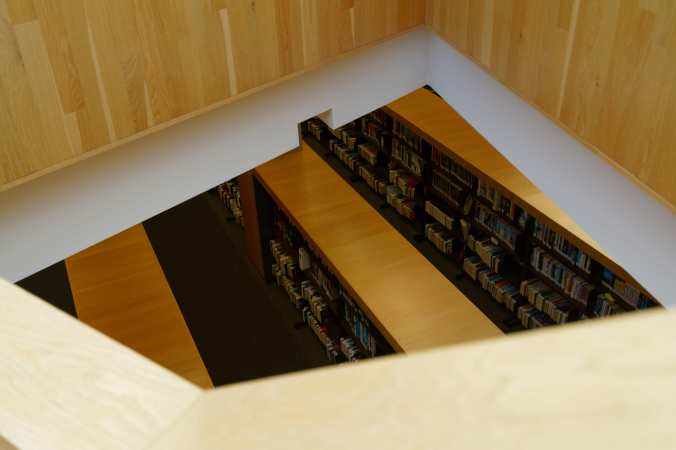

Building has proceeded slowly in the Central Business District — Christchurchians grumble about it, then shrug, adding, it’s a great city. The CBD has been divided into precincts for retail, “innovation” (which I gather means hi-tech), health, performing and visual arts, and “justice and emergency services”. Dozens of large new buildings are under construction: a new metro sports facility, a new central library, a new convention center. A new transit and bus station opened recently.

Building has proceeded slowly in the Central Business District — Christchurchians grumble about it, then shrug, adding, it’s a great city. The CBD has been divided into precincts for retail, “innovation” (which I gather means hi-tech), health, performing and visual arts, and “justice and emergency services”. Dozens of large new buildings are under construction: a new metro sports facility, a new central library, a new convention center. A new transit and bus station opened recently.

A couple of days of walking around the city suggested that the Little Black Hut’s design finesse was not unusual: most homes are small, but the detailing and compositional sensibility even in little cinder block, wood, or corrugated-metal-sided homes looks pretty well done.

A couple of days of walking around the city suggested that the Little Black Hut’s design finesse was not unusual: most homes are small, but the detailing and compositional sensibility even in little cinder block, wood, or corrugated-metal-sided homes looks pretty well done.

How little we missed the “sense of history” so prized amongst Americans! Running into the few remaining Victorian houses, grand and modest, provided enjoyment but not the sense of relief one finds when stumbling upon even modest historic structures in the United States. What we found in Christchurch substantiates the argument I advanced in WtYW that the problem in the US built environment is less old (better)-versus-new (clueless), but the poor design quality and craftsmanship of new construction. In Christchurch, high quality new homes, commercial, and retail buildings could be found everywhere. Even the mediocre buildings are good.

How little we missed the “sense of history” so prized amongst Americans! Running into the few remaining Victorian houses, grand and modest, provided enjoyment but not the sense of relief one finds when stumbling upon even modest historic structures in the United States. What we found in Christchurch substantiates the argument I advanced in WtYW that the problem in the US built environment is less old (better)-versus-new (clueless), but the poor design quality and craftsmanship of new construction. In Christchurch, high quality new homes, commercial, and retail buildings could be found everywhere. Even the mediocre buildings are good.  Stay tuned, then, for the new iteration of New Zealand’s garden city — and dream.

Stay tuned, then, for the new iteration of New Zealand’s garden city — and dream. The exception was Casablanca, but Fez, people tell me, confers this impression with even greater intensity. In its sense of arrested time, Morocco felt very different from other developing societies I’ve encountered. Take India. In India, people’s lives are saturated with tradition, but they do not, or at least did not appear to me to reject modernity. In some of Morocco’s most distant reaches, people seem only dimly aware that modern societies even exist. What are they watching on satellite TV?

The exception was Casablanca, but Fez, people tell me, confers this impression with even greater intensity. In its sense of arrested time, Morocco felt very different from other developing societies I’ve encountered. Take India. In India, people’s lives are saturated with tradition, but they do not, or at least did not appear to me to reject modernity. In some of Morocco’s most distant reaches, people seem only dimly aware that modern societies even exist. What are they watching on satellite TV?

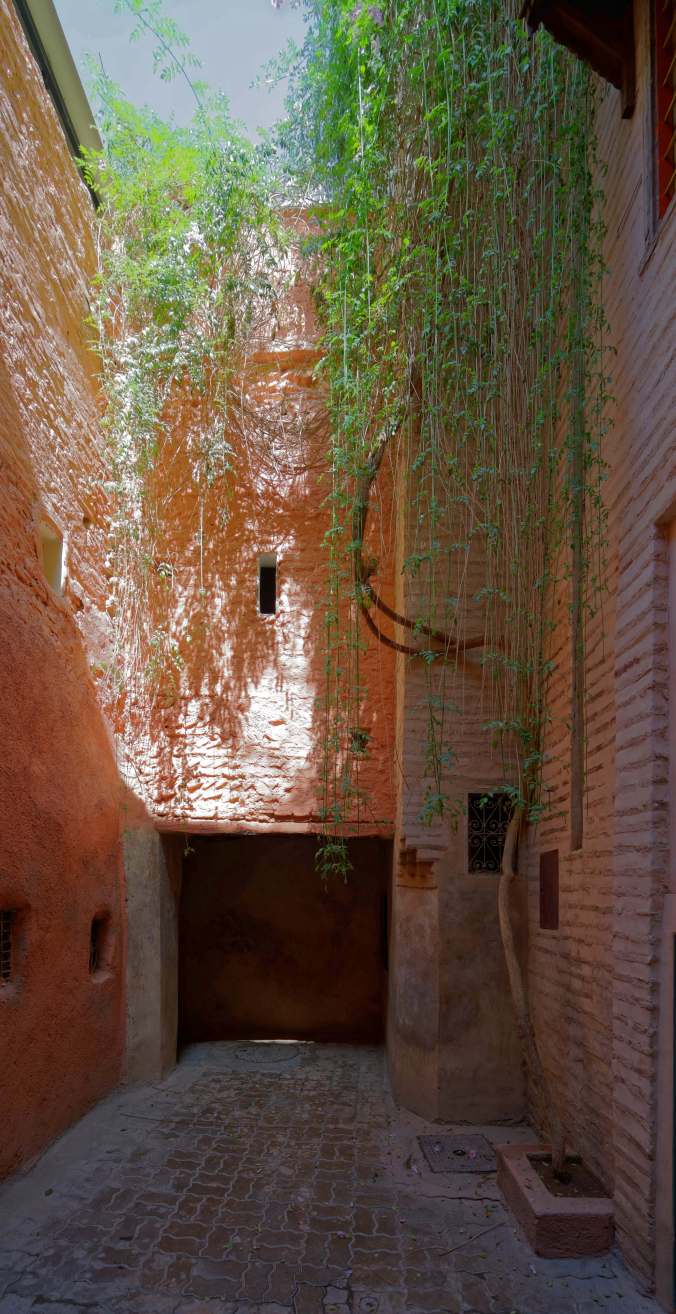

Sometimes, in larger buildings, internal rooms with tiny windows butt up onto rooms opening onto subcourtyards with skylit roofs.

Sometimes, in larger buildings, internal rooms with tiny windows butt up onto rooms opening onto subcourtyards with skylit roofs. Spatial organization, spatial sequences – all are straightforward, even banal. (If the site varies topographically, sometimes there’s a little more action, as in the palace at Telouet.) So the colorful, intricate patterns constitute the only means of arresting our visual interest — or, to invert the formulation, to compensate for the lack of design complexity.

Spatial organization, spatial sequences – all are straightforward, even banal. (If the site varies topographically, sometimes there’s a little more action, as in the palace at Telouet.) So the colorful, intricate patterns constitute the only means of arresting our visual interest — or, to invert the formulation, to compensate for the lack of design complexity. In no place we visited did that differ.

In no place we visited did that differ.