FROM all the building going on in Sydney and Melbourne, one gets the clear impression as far as real estate development is concerned, good money is being made. Yet unlike what too often happens in the States, private profit appears not to come at the expense of an investment in the shared social spaces that are somewhat loftily (and too inchoately) called a city’s public realm. (For an instructive and dispiriting contrast to what we found in Australia, read this, on the ongoing disintegration of New York City’s subway system.) Here, it seems, it’s not one or the other, but both. Public and private. Everybody wins.

The plenitude and variety of welcoming open spaces in Sydney and Melbourne’s newer (or newish) developments suggest that those in charge of urbanism operate with both a robust commitment and sufficient resources to ensure that cities offer pedestrian amblers-around many opportunities to choose from, on and off the street, to meet a friend or just take a midday pause. Places where strangers graze elbows without stepping on one another’s toes.

Architecturally, some are distinctive, others not. Melbourne’s Federation Square, below (completed ca. 2003), epitomizes the complexity of this relationship between urbanism and architecture — and now, it’s become the focus of this never-ending discussion about balancing private and public space, as Apple proposes demolishing one of its buildings to erect a new retail store (read about that here).  Comprised of a series of buildings, each a slightly different but equally horrible bastardization of some also-horrible Daniel Liebeskind-ish idea (he was on the jury that chose the principal designers), Federation Square nevertheless contains many deep pockets of agreeable urbanity, woven into the eye-smarting silliness of its architecture.

Comprised of a series of buildings, each a slightly different but equally horrible bastardization of some also-horrible Daniel Liebeskind-ish idea (he was on the jury that chose the principal designers), Federation Square nevertheless contains many deep pockets of agreeable urbanity, woven into the eye-smarting silliness of its architecture.

Tourists, by definition peripatetic, will find the complex difficult to avoid. Each day and time we found ourselves in Federation Square, its low-slung and high-rising steps and sitting areas, its recessed spatial eddies and quarkily-configured common spaces, teemed with riots of people, color, and activity. Amphitheater-like steps offer up seating areas for school kids eating lunch, mothers on outing with toddlers in strollers, all manner of passers-by and lingerers.  In front of the Christmas tree, we spotted a woman swathed in hajib posing with her daughter for a picture. Later, discussing the ways Australia’s changed in the past two decades, a remarkably voluble Uber driver — who once worked as an advocate for occupational health and safety in the mining industry — told us that the country’s welcoming immigration policies has created a far more tolerant, open society than the one in which he was raised.

In front of the Christmas tree, we spotted a woman swathed in hajib posing with her daughter for a picture. Later, discussing the ways Australia’s changed in the past two decades, a remarkably voluble Uber driver — who once worked as an advocate for occupational health and safety in the mining industry — told us that the country’s welcoming immigration policies has created a far more tolerant, open society than the one in which he was raised.

Compositionally, the Federation Square complex offers up nice moments, here and there. Such as this one, on a staircase tucked off the busy, main thoroughfare, where a maintenance worker on break set her blue knapsack down and started in on checking her cell phone, not even bothering to remove her latex gloves.

Among the urbanistically-preoccupied, the best known urban project in Australia, besides Sydney’s Opera House, remains Jan Gehl Associates’ transformation of Melbourne’s Central Business District from a litter-strewn, post-5pm-and-weekend urban graveyard into a vibrant, crowded, see-and-be-seen, free-for-all (I seem to be on some kind of adjectival run) place of urban congregation.  The most clever thing Gehl did was to link together a series of unprepossessing back alleys and reconfigure their street-level frontage to admit teeny-tiny storefronts, just the right size to create arrays of specialized restaurants and shops.

The most clever thing Gehl did was to link together a series of unprepossessing back alleys and reconfigure their street-level frontage to admit teeny-tiny storefronts, just the right size to create arrays of specialized restaurants and shops.  These new open-air pedestrian malls were threaded into the pathways of two preexisting historic shopping arcades; this one, below, even more exquisite than the photo conveys, opened in 1870.

These new open-air pedestrian malls were threaded into the pathways of two preexisting historic shopping arcades; this one, below, even more exquisite than the photo conveys, opened in 1870.

Royal Arcade, Melbourne

As Danny and I traversed the entire loop, courtesy of a map obtained from the tourist information bureau, I idly mused whether it might be possible to spend all the money earned in a month in a single afternoon walk. Restaurants, art galleries (including one selling what its proprietors claimed were original drawings by Dr. Seuss), clothing and jewelry and hand-mixed cosmetic stores. Certainly the retinue of shopkeepers and restauranteurs milling around, expectantly, held out hope that wallets would empty, and empty again. Ours didn’t, but we enjoyed the show.

Sydney’s Central Business District retains more of its Victorian-era architecture; the newer developments we sought out lie in neighborhoods at a remove from the city’s neverending, serpentine shoreline. In Chippendale, not far from the University of Technology Sydney campus, we were stopped short in our tracks by the sight of this spectacular, justly celebrated high-rise by Jean Nouvel, designed in collaboration with Foster & Partners and Patric Blanc, the French botanist who invented the green wall. Pretentiously, audaciously named One Central Park (the developer’s promotional materials represent it, fatuously, as a vertical version of New York City’s emerald gem), it’s a luxury residential-cum-retail complex defining one edge of a block-sized green, something between a plaza and a park. The day we visited, the plaza-park bubbled with shoppers en route to the supermarket, construction workers on lunch break, seeking shade. The attractive multilevel retail complex encircles a green-walled atrium filled with cascading natural light, and spinning around the void was a blur of parcels leading their human owners hither and yon. How did the architects manage to project natural light so deep into a multistory, partially underground atrium? That large shimmering cantilever projecting off the façade: it’s a metal grid hung with mirrors programmed to follow the rays of the sun, directing and redirecting them into the atrium below.

Streetside, the building’s green facades project a soft-edged, appealing presence, and Blanc made sure that all the plants are native to Australia.

We continue to pursue green, especially in cities, even with New Zealand long behind us. Neither Sydney nor Melbourne disappointed. Foremost among the urban pastorals is landscape architect Peter Walker’s newly opened Barangaroo Reserve Park. Stunning.

10,000 blocks of rich, creamy sandstone create a graduated, semi-permeable shoreline edge (professionals call this riprap) that helps to mitigate flooding; Walker, recognizing the stone’s beauty, made it the design datum for the park, using it for much else, too.

Sitting stones (left).

Benches, parapets, stairs, terracing.

The Barangaroo Reserve opened only recently. The day we visited it was practically empty, but that’s because it’s currently pretty inaccessible, surrounded by a busy thoroughfare and a huge construction site. Soon enough, I predict, it will earn its rightful place as a treasured part of Sydney’s urban fabric. You can read more about it here.

Finally, the magical Botanic Gardens in both cities.

Just one prospect of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne.

This also displays astonishing set pieces in the form of weird, wonderful trees.

A stubby, fat palm that defiantly sat in our path.

A stubby, fat palm that defiantly sat in our path.  A gossamer, red-berried wonder that you spied only if you looked straight up.

A gossamer, red-berried wonder that you spied only if you looked straight up.

One with gnarly-fingered branches encased in bark so deeply incised that half your hand would fit into each of its grooves.

One with gnarly-fingered branches encased in bark so deeply incised that half your hand would fit into each of its grooves.  And one tree that reminded me of Edward Weston’s wonderful green pepper photographs, or, for a more recent reference, of Del Kathryn Barton’s exuberantly multi-breasted women.

And one tree that reminded me of Edward Weston’s wonderful green pepper photographs, or, for a more recent reference, of Del Kathryn Barton’s exuberantly multi-breasted women.

All in all, Australians seem to appreciate the wonders of their cityscapes and their landscapes. More than once, we found its soft surfaces celebrated in the hard ones.

The country’s two principal cities make a good exemplar for urban livability, one that other cities and countries might take a good, long look at– and take heed.

— Sarah

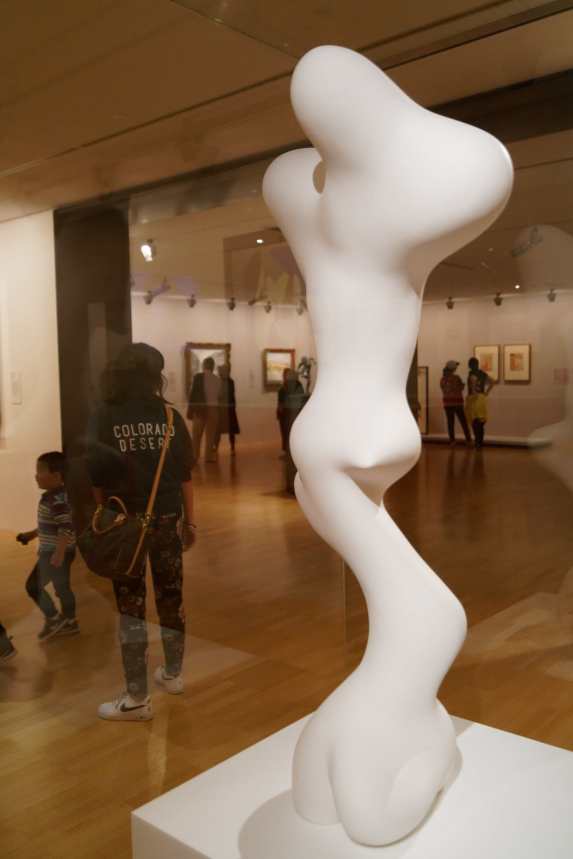

Then we practically ran straight into one of the best Hans (aka Jean) Arp sculptures, from his “Growth” series, that I’ve ever encountered. I was really tempted to hug it.

Then we practically ran straight into one of the best Hans (aka Jean) Arp sculptures, from his “Growth” series, that I’ve ever encountered. I was really tempted to hug it.

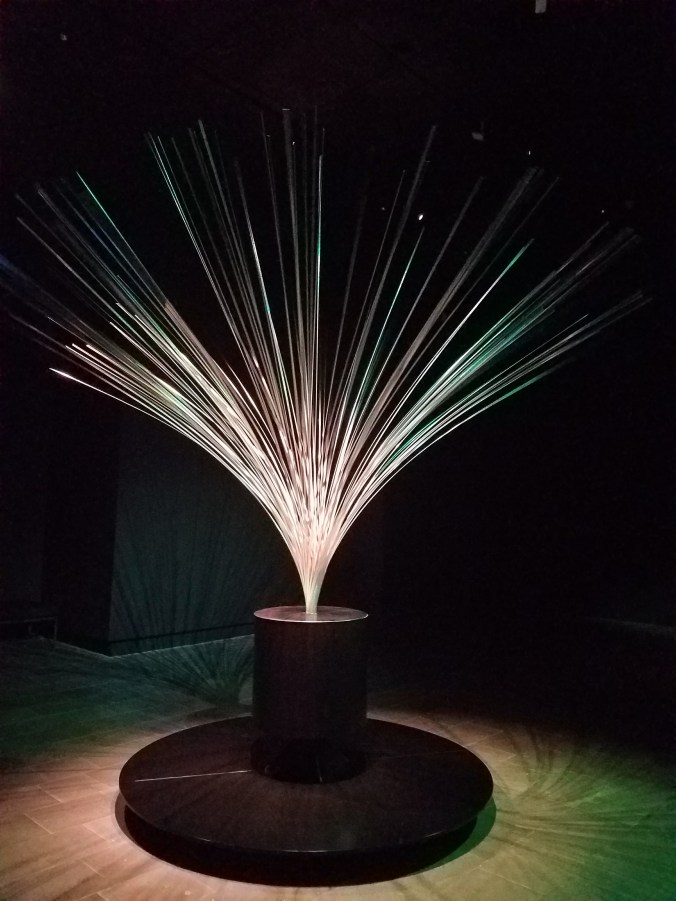

Since mirrors can be used to visually diminish the scale of the object they reflect, you get to experience the piece both as it envelops you, spreading majestically over your head and bleeding into your peripheral vision, and at the same time, regard its entirety by glancing toward the silvery pools of light near your feet.

Since mirrors can be used to visually diminish the scale of the object they reflect, you get to experience the piece both as it envelops you, spreading majestically over your head and bleeding into your peripheral vision, and at the same time, regard its entirety by glancing toward the silvery pools of light near your feet.

We departed Sydney ahead of schedule, after but a few days, to a recuperative place, Palm Beach, an hour north, where the din (noise bothered him) and bustle of the city were replaced by the quietude and seaside rhythms of nature.

We departed Sydney ahead of schedule, after but a few days, to a recuperative place, Palm Beach, an hour north, where the din (noise bothered him) and bustle of the city were replaced by the quietude and seaside rhythms of nature.

The most obtrusive sounds came from the many birds flying around, especially in the early morning, with some (most notably, a faithful white cockatoo with a yellow crest), to our thrill, visiting our veranda. Gideon loved our place there and what constituted the thereness of there.

The most obtrusive sounds came from the many birds flying around, especially in the early morning, with some (most notably, a faithful white cockatoo with a yellow crest), to our thrill, visiting our veranda. Gideon loved our place there and what constituted the thereness of there.

explored the magnificent Royal Botanic Gardens,

explored the magnificent Royal Botanic Gardens,

and walked and looked, which, after all, is just about our favorite urban activity – especially when the walking and looking amply reward.

and walked and looked, which, after all, is just about our favorite urban activity – especially when the walking and looking amply reward. To give Queenstown its due, it is perhaps the most beautiful and monumental setting of any urban area (it’s a small one) we have seen.

To give Queenstown its due, it is perhaps the most beautiful and monumental setting of any urban area (it’s a small one) we have seen.

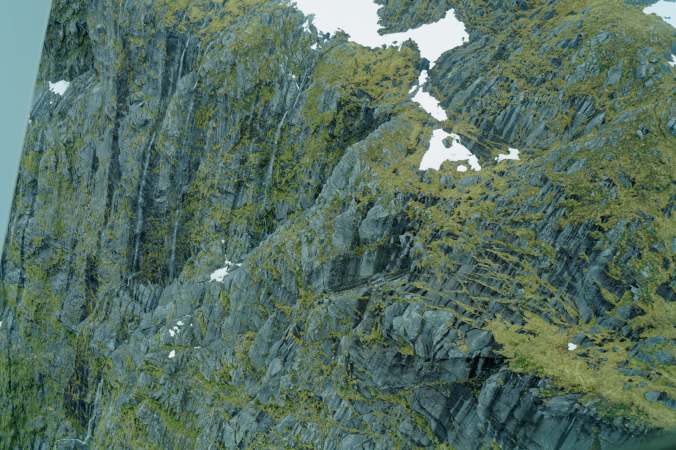

The landscapes of the region we have justly gushed (never enough) about. Even the humdrum among them – the city park, and an elevation-static walk starting in Queenstown along the lake and then beyond – are memorable and prospectively never tiring. Our one disappointment, not being able to walk/hike the three-day Routeburn Track, reputably among the most exquisite in New Zealand, owing to a minor injury Gideon sustained, turned into a compensatory boon of us getting to explore by car and foot more of the Queenstown region. After leaving the urban and in its own way urbane area of Queenstown, we drove through the seductive temperate rainforest

The landscapes of the region we have justly gushed (never enough) about. Even the humdrum among them – the city park, and an elevation-static walk starting in Queenstown along the lake and then beyond – are memorable and prospectively never tiring. Our one disappointment, not being able to walk/hike the three-day Routeburn Track, reputably among the most exquisite in New Zealand, owing to a minor injury Gideon sustained, turned into a compensatory boon of us getting to explore by car and foot more of the Queenstown region. After leaving the urban and in its own way urbane area of Queenstown, we drove through the seductive temperate rainforest

and mountainscapes of the west coast, fittingly named West Coast, and then across the mountain isthmus of Arthur’s Pass to a more conventional and more distinctive urban experience of Christchurch.

and mountainscapes of the west coast, fittingly named West Coast, and then across the mountain isthmus of Arthur’s Pass to a more conventional and more distinctive urban experience of Christchurch.

where we strolled for a few hours thinking of an architecturally unsullied Miami Beach and disputating the desirability of returning to Napier someday for a longer stint, before heading off by car to Tongariro, and its justly famous transalpine tramp. After four days of our rural and hiking wonders of Tongariro

where we strolled for a few hours thinking of an architecturally unsullied Miami Beach and disputating the desirability of returning to Napier someday for a longer stint, before heading off by car to Tongariro, and its justly famous transalpine tramp. After four days of our rural and hiking wonders of Tongariro  (Sarah: “I would do that hike every year”) and Rotorua – both of Hobbit/Lord of the Rings fame – we finished off our New Zealand romp with two solid days in Auckland’s Viaduct area, with a splendid view of the harbor, urbanity, and enough worthy activities to keep us happy.

(Sarah: “I would do that hike every year”) and Rotorua – both of Hobbit/Lord of the Rings fame – we finished off our New Zealand romp with two solid days in Auckland’s Viaduct area, with a splendid view of the harbor, urbanity, and enough worthy activities to keep us happy.

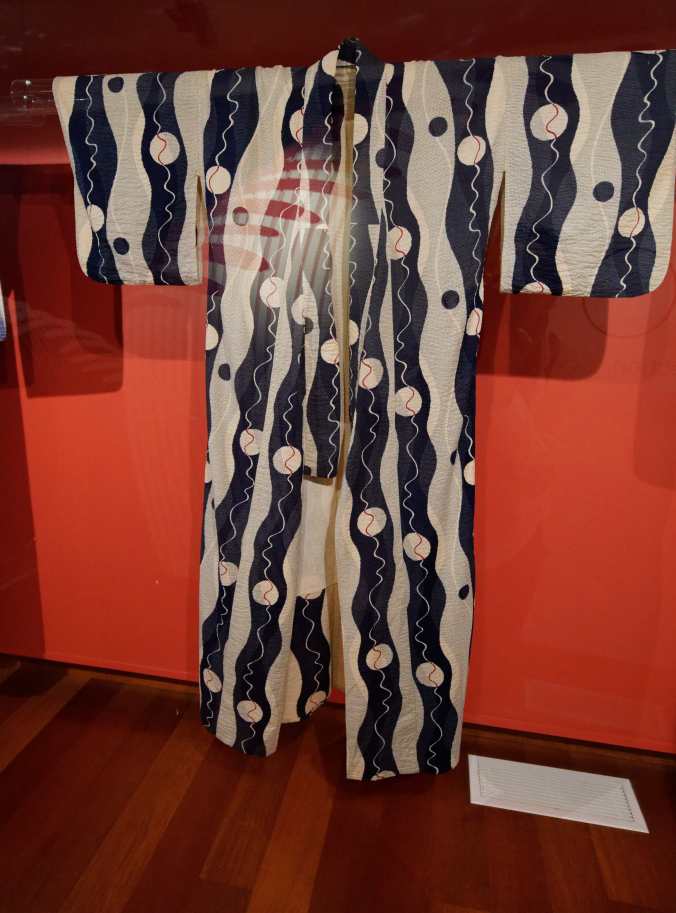

and in the a Napier museum, receiving the unexpected pleasure of being introduced to a merging of arts we had not imagined in the body (really body-covers) of historic Art Deco

and in the a Napier museum, receiving the unexpected pleasure of being introduced to a merging of arts we had not imagined in the body (really body-covers) of historic Art Deco

immersing ourselves in the experience of the most magnificent landscapes of nature’s pacific and tumultuous offerings, getting a taste or more of the largest (Auckland, 1.5M), third largest (Christchurch, 400K), sixth largest (Napier, 130K), tenth largest (Rotorua, 60K), and barely-large-enough-to-be-one, placing 27th (Queenstown, 15K) city, and many larger and smaller towns in-between, and taking pleasure in some of the finer products of human creativity. Everywhere and without exception, the New Zealanders were friendly, helpful, informed, and well-spoken in, at least to me, their charmingly accented English. They appear to know that they have something extraordinary going for them,

immersing ourselves in the experience of the most magnificent landscapes of nature’s pacific and tumultuous offerings, getting a taste or more of the largest (Auckland, 1.5M), third largest (Christchurch, 400K), sixth largest (Napier, 130K), tenth largest (Rotorua, 60K), and barely-large-enough-to-be-one, placing 27th (Queenstown, 15K) city, and many larger and smaller towns in-between, and taking pleasure in some of the finer products of human creativity. Everywhere and without exception, the New Zealanders were friendly, helpful, informed, and well-spoken in, at least to me, their charmingly accented English. They appear to know that they have something extraordinary going for them,  and, generous lot that they are — here’s a woman who runs a weekly open-air soup kitchen in Auckland, offering us a meal —

and, generous lot that they are — here’s a woman who runs a weekly open-air soup kitchen in Auckland, offering us a meal —  they don’t mind sharing the natural and urbanistic wealth.

they don’t mind sharing the natural and urbanistic wealth. One place that succeeded in earning a top spot in our greatest hits album (maybe that’s this blog) was in the volcanic Rotorua region, which includes the Tarewera, a volcano that has erupted 5 times in last 18,000 years (one so extreme that it cast volcanic dust as far away as Greenland), as well as the Waimangu. The last major eruption of the volcanic craters all along Waimangu valley was in 1886, which falls easily within the era of photography. The

One place that succeeded in earning a top spot in our greatest hits album (maybe that’s this blog) was in the volcanic Rotorua region, which includes the Tarewera, a volcano that has erupted 5 times in last 18,000 years (one so extreme that it cast volcanic dust as far away as Greenland), as well as the Waimangu. The last major eruption of the volcanic craters all along Waimangu valley was in 1886, which falls easily within the era of photography. The  The Waimangu regaled us with hot waters,

The Waimangu regaled us with hot waters, and hot (and cool, in both senses of the word) colors,

and hot (and cool, in both senses of the word) colors,

and with a tiny, even cute little geyser (below, at the left side of the image), wholly unlike the more conventional tower of water we saw a few years ago outside of Reykjavik in the gushing font that gave its name to this natural though relatively rare phenomenon, Geysir.

and with a tiny, even cute little geyser (below, at the left side of the image), wholly unlike the more conventional tower of water we saw a few years ago outside of Reykjavik in the gushing font that gave its name to this natural though relatively rare phenomenon, Geysir.

that reminded Sarah of one of her newish-ly favorite paintings, by Gustav Klimt, which we saw in an exhibition of landscape art from The Paul G. Allen Family Collection at the Phillips Collection in Washington DC.

that reminded Sarah of one of her newish-ly favorite paintings, by Gustav Klimt, which we saw in an exhibition of landscape art from The Paul G. Allen Family Collection at the Phillips Collection in Washington DC.

offering a skylet-high tree walkway,

offering a skylet-high tree walkway,  right outside the city of Rotorua, the forest the result of a tree growing commercial experiment which brought the trees over from California way-back-when-enough that the (skinny) redwoods reach (from unverified memory) three hundred feet and more.

right outside the city of Rotorua, the forest the result of a tree growing commercial experiment which brought the trees over from California way-back-when-enough that the (skinny) redwoods reach (from unverified memory) three hundred feet and more.

make Maya Lin’s land-sculpture in Storm King Sculpture Park,

make Maya Lin’s land-sculpture in Storm King Sculpture Park, which we once admired, a bit self-mocking. Driving through hours of such hillocks made for the greenest mad-undulating landscape this side of our known experience.

which we once admired, a bit self-mocking. Driving through hours of such hillocks made for the greenest mad-undulating landscape this side of our known experience. Sarah’s favorite tree — its name escapes us — was that black-barked fern, plentiful in much of New Zealand, which, in rain-forest-y

Sarah’s favorite tree — its name escapes us — was that black-barked fern, plentiful in much of New Zealand, which, in rain-forest-y  New Zealanders, with their seemingly infinite capacity to charm, charmingly call trekking or hiking “tramping”, which constitutes something of a national pastime. Tourist brochures and government-sponsored websites alike advertise the Tongariro Alpine Crossing as the best one-day tramp in the country. Not for the faint of heart, though. It’s 19.4 kilometers (nary a water source along the way), with official estimates advising that hikers to plan on between six and eight hours, with the ominous addendum, “depending upon your condition”. You are also repeatedly reminded to pack for different kinds of weather events: you can shiver in pelting sleet and sweat in blazing rays of sun in a single day. Or you can find yourself at the peak of a dry, sandy, 10-foot-wide ridge huddling against 65 mile-per-hour winds, as happened the

New Zealanders, with their seemingly infinite capacity to charm, charmingly call trekking or hiking “tramping”, which constitutes something of a national pastime. Tourist brochures and government-sponsored websites alike advertise the Tongariro Alpine Crossing as the best one-day tramp in the country. Not for the faint of heart, though. It’s 19.4 kilometers (nary a water source along the way), with official estimates advising that hikers to plan on between six and eight hours, with the ominous addendum, “depending upon your condition”. You are also repeatedly reminded to pack for different kinds of weather events: you can shiver in pelting sleet and sweat in blazing rays of sun in a single day. Or you can find yourself at the peak of a dry, sandy, 10-foot-wide ridge huddling against 65 mile-per-hour winds, as happened the

Circumventing the Red Crater (you couldn’t actually ascend it) brought you into view of the vaginal-looking orifice from which all that lava spewed during its last eruption. From there, you began your multi-houred descent. Around one bend, you see this: the Emerald Lakes (at right). At left-center, in middle distance, you can just glimpse the Blue Lake, and behind it in the horizon, Lake Tapuo, which is a caldera of a different volcano, about 90 miles away.

Circumventing the Red Crater (you couldn’t actually ascend it) brought you into view of the vaginal-looking orifice from which all that lava spewed during its last eruption. From there, you began your multi-houred descent. Around one bend, you see this: the Emerald Lakes (at right). At left-center, in middle distance, you can just glimpse the Blue Lake, and behind it in the horizon, Lake Tapuo, which is a caldera of a different volcano, about 90 miles away.

and here’s the sunrise that greeted us in the morning.

and here’s the sunrise that greeted us in the morning.

seeing those mountains shooting straight out of its deep, black waters is unforgettable.

seeing those mountains shooting straight out of its deep, black waters is unforgettable.