Six months ago, I wouldn’t have been able to locate Namibia on an unmarked map, except to say that it’s in Africa. Danny and Gideon collaborated intensely on this part of the trip, so I decided to simply sit in the passenger seat and enjoy the view of the road, letting them decide upon places to skip and places to stop, and for how long.

The flight from Cape Town to Namibia’s capital, Windhoek, took us up and over some of the Atlantic coastline before circling back over land. No, dirt. Or dirt and sand. As we neared our destination, dozens of what looked like dirt paths appeared on the surface of this parched land, lines stretching miles from one location to another without any clear signs of why one would embark upon a journey where the road began, nor travel it, nor reach the equally vacant destination visible at its other end.

Those dirt paths turned out to be roads, and they constitute most of Nambia’s transportation infrastructure.  Only one paved (in local argot, sealed) highway, admittedly with arterial branches, stretches from north to south; a second, west-east, connects the adjacent towns of Walvis Bay and Swakopmund on the Atlantic with Windhoek. This one runs through the most economically developed regions of the country. Mostly, mines: diamond mines, copper mines, tungsten mines, and two of the top-ten uranium mines in the world.

Only one paved (in local argot, sealed) highway, admittedly with arterial branches, stretches from north to south; a second, west-east, connects the adjacent towns of Walvis Bay and Swakopmund on the Atlantic with Windhoek. This one runs through the most economically developed regions of the country. Mostly, mines: diamond mines, copper mines, tungsten mines, and two of the top-ten uranium mines in the world.

Hiss, Mom, Gideon advised as we passed it. That’s what they make nukes with.

The first time I’d heard the name Swakopmund was when we asked Jan, the proprietor of the Witsieshoek Lodge in South Africa’s Drakensburg, where he came from. He replied, uttering his hometown’s name with swagger – SWA KUP MUND—and from then on Danny, Gideon and I could utter the word no other way. As if this remote city – town, really—were in actuality the unspoken center of the earth. “It’s a strange place,” Jan continued. “Completely German. Like a little German city, set on the coast of the Atlantic in the emptiest part of Southern Africa.”

That sold me. We must go. We’d planned to anyway, because it self-advertises as the extreme adventure capital of Southern Africa, and Gideon was determined to hurl himself out of an airplane in tandem with some stranger to whom he would entrust his very life. (As it turned out, he never did. Too cloudy, too cold.) But my determination became relevant during our visit to Sossusvlei, when the possibility of skipping Swakopmund arose more than once. And not without reason. The driving distances in Namibia seem absolutely endless: desolate hours upon hours pass, and you begin to feel as though you absolutely absolutely MUST be approaching your destination, when a quick check of the road map or the GPS ETA reveals that you’re less than halfway there, and before you lies miles, endless miles, of scrub brush, heat, and emptiness.

The wide, long, rattling journey from Sossusvlei to Swakopmund will surely always be one of most beautiful drives I have ever had the good fortune to enjoy. It’s not spectacular, like the drive from the San Francisco Bay Area up to Sea Ranch on the Pacific Coast, or the drive from Geneva to Lausanne. You really have to watch. I passed the hours gazing out onto these often flat, sometimes rolling expanses of land, parsing out how the sense of deep space came mostly from variations in color saturation, hue, and temperature,

The wide, long, rattling journey from Sossusvlei to Swakopmund will surely always be one of most beautiful drives I have ever had the good fortune to enjoy. It’s not spectacular, like the drive from the San Francisco Bay Area up to Sea Ranch on the Pacific Coast, or the drive from Geneva to Lausanne. You really have to watch. I passed the hours gazing out onto these often flat, sometimes rolling expanses of land, parsing out how the sense of deep space came mostly from variations in color saturation, hue, and temperature,  and noticing subtle shifts in the layered bands of browns, grays, thin, struggling greens.

and noticing subtle shifts in the layered bands of browns, grays, thin, struggling greens.  When the arid ground shifted from flat and sandy to inclined and rockier, my heart leapt, delighting in the textural variation.

When the arid ground shifted from flat and sandy to inclined and rockier, my heart leapt, delighting in the textural variation. Nothing, nothing, nothing. Until you realize that nothing is something. Burrow into these muted colors and thin layers, into this topography. This landscape settles inside you, then stays.

Nothing, nothing, nothing. Until you realize that nothing is something. Burrow into these muted colors and thin layers, into this topography. This landscape settles inside you, then stays.

We’re going to that little German city, I kept thinking, perched on a remote coast of southwest Africa.

A little history here. Germany unified much later than many other European countries and, mainly landlocked, had no fleet. So by the 1880s, whereas England, France, and the Netherlands all had multiple, economically vibrant colonies begotten during the so-called Scramble for Africa, Germany, an aspirant to world power, was bereft.

Southern Africa had been almost completely carved up with the exception of the land that is now Namibia. This arid desert was unclaimed, except of course by the peoples who had always lived there, the Herero, Nama and San tribes, who lived in mutual enmity, competing over land and resources. Germany settled, and in the subsequent years, grabbed more, then more. The indigenous peoples had the audacity to believe that the land they and their ancestors had always inhabited was in fact theirs. Despite their enmity, they unified, forming an army to rebel against the German occupation. The German colonists’ response was swift, and brutal: by the end of 1905, somewhere between 24,000 and 100,000 Herero and Nama had been starved or slaughtered.

The end of the Swakopmund-bound drive comes suddenly. Civilization!

Paved streets. A new shopping mall under construction, outside of town. Two-story concrete frame buildings – nearly everything is concrete frame, not steel– housing the warehouses and offices of various local companies.

Paved streets. A new shopping mall under construction, outside of town. Two-story concrete frame buildings – nearly everything is concrete frame, not steel– housing the warehouses and offices of various local companies.

Then, suddenly again: Victorian buildings everywhere. Some sedate in their detailing, others florid.

Notice Atlas on the corner, holding up the world

Churches, commercial blocks, a post office.

At the edge of the commercial area, near the shore, sits a little enclosed complex with an arcaded courtyard and a charming lookout tower; once, it housed a boarding school.

At the edge of the commercial area, near the shore, sits a little enclosed complex with an arcaded courtyard and a charming lookout tower; once, it housed a boarding school.

Tastefully restored arts and crafts detailing grace the pilaster capitals and string courses.

Most of the earliest buildings are proudly dated: 1904.

They slaughter the local population, then build, Danny said grimly. The genocide ended in 1905. Later that same day in the main public square, we ran across the gruesome statue Danny mentioned in the previous post, and then, nearby, an equally unsettling sight: this monument commemorating German soldiers who died in both World War I — AND World War II — surrounded by a small little fence.  To locals, this place, like the graciously-planted, serpentine beachside pathways, was just another instance of tidy Swakopmund’s gracious provision of landscaping and street furniture.

To locals, this place, like the graciously-planted, serpentine beachside pathways, was just another instance of tidy Swakopmund’s gracious provision of landscaping and street furniture.

Beachfront landscaping, with bike path at left

Shopping typically figures hardly at all into our traveling lexicon, but the merchants of Swakopmund have figured out that while its more adventurous visitors risk their lives on this or that perilous thrill, their more sober companions might well seek alternative forms of entertainment. We found a nice pedestrian shopping area, new, but in the Swakopmundian, quasi-Germanic mode.  In it was an excellent new-and-antiquarian bookstore, filled with German-speaking latte-drinkers and German-language paperbacks.

In it was an excellent new-and-antiquarian bookstore, filled with German-speaking latte-drinkers and German-language paperbacks.  We poked around for a good half hour, turning up a battered Herero-German dictionary, published in 1904.

We poked around for a good half hour, turning up a battered Herero-German dictionary, published in 1904.

Must have been early in the year.

–Sarah

We gazed upon them. We walked past and around them. We climbed them. We (Gideon and Sarah) stood astride them and surveyed the dominion. Gideon lay on them. He even, unsuccessfully, tried to roll down them, only to discover that they enveloped and captured his body as they had his imagination and soul.

We gazed upon them. We walked past and around them. We climbed them. We (Gideon and Sarah) stood astride them and surveyed the dominion. Gideon lay on them. He even, unsuccessfully, tried to roll down them, only to discover that they enveloped and captured his body as they had his imagination and soul.

reassembling at our SUV, driving further into the dunescape, taking a four-wheel drive sand-ferry for four kilometers, and trekking afoot twenty minutes deeper up into the dunes, we came upon the nearly sacralized desert landscape, foremost among desert moments in the world, of Deadvlei — to wander among, behold, and contemplate, and, in Sarah’s and my case, talk about the dune-flanked and framed magnificent salt pan

reassembling at our SUV, driving further into the dunescape, taking a four-wheel drive sand-ferry for four kilometers, and trekking afoot twenty minutes deeper up into the dunes, we came upon the nearly sacralized desert landscape, foremost among desert moments in the world, of Deadvlei — to wander among, behold, and contemplate, and, in Sarah’s and my case, talk about the dune-flanked and framed magnificent salt pan

and anything, which was plenty, that the embodied mind of being there conjured up for the hour or so that we basked in this and our singularity, and in our commonality of sharing this place and our lives.

and anything, which was plenty, that the embodied mind of being there conjured up for the hour or so that we basked in this and our singularity, and in our commonality of sharing this place and our lives.

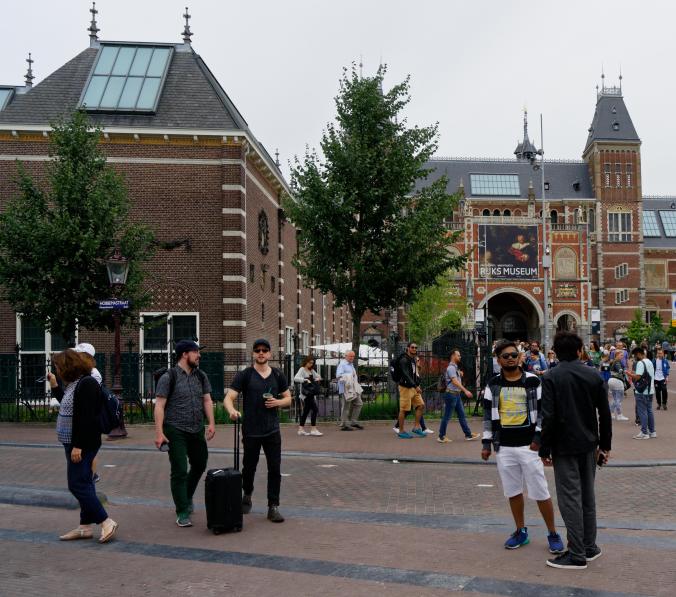

We had a fine day and previous evening in Oslo, mostly walking and taking in its distinctive urbanity and its fabric, mainly known as buildings.

We had a fine day and previous evening in Oslo, mostly walking and taking in its distinctive urbanity and its fabric, mainly known as buildings.

In the early afternoon, just as it was beginning to rain, we visited and marveled at Snohetta’s renowned Opera House.

In the early afternoon, just as it was beginning to rain, we visited and marveled at Snohetta’s renowned Opera House.

Sarah and I set out on our adventure with the purpose of writing books, one by her and one by me, very different in character, each possible only through this long journey. More on them in a moment. We also set out committed to the writerly experiment of this let-the-spirit-move-us collaborative blog, which includes Gideon, who, I hope, will make his entry here soon and thereafter frequently. For Sarah and for me (about Gideon, who also has other writing projects, I’m not sure), the question of what goes where is live, and, at least for me, has not been resolved clearly.

Sarah and I set out on our adventure with the purpose of writing books, one by her and one by me, very different in character, each possible only through this long journey. More on them in a moment. We also set out committed to the writerly experiment of this let-the-spirit-move-us collaborative blog, which includes Gideon, who, I hope, will make his entry here soon and thereafter frequently. For Sarah and for me (about Gideon, who also has other writing projects, I’m not sure), the question of what goes where is live, and, at least for me, has not been resolved clearly.  Roughly speaking, my schema is to offer you accounts and observations about the world out there which we encounter on our carefully chosen itinerary of barely scratching the world’s surface, even with a year of scratching at our disposal. The inner workings and inter-workings of the three of us – what it is like to travel with two loved ones for a year, and how the many and ongoing encounters with one another and with the offerings and demands of the world we will wend our way through affect and change us as individuals and in our relationships as parents and child, as married people, as individuals positioned differently in the ever-changing arrays of living – these things about us are the stuff and soul of the book. The rub might be obvious: the line, actually lines demarcating what’s out there from what’s in here (the family circle and each of our minds and hearts) is hard to draw, especially as the inside is implicated in the outside, most essentially because both constitute and are filtered through experience, thought, and language. (Taking and posting photos – Sarah’s and Gideon’s domains – are more clear cut.) So, deciding what’s in and out of the blog, because what constitutes the in(side) and the out(side) of the respective worlds we are living and seeking to understand is often indeterminate, is an ongoing and inherently messy and probably shifting process which I am negotiating with that very tough and a bit ambivalent negotiator, myself. As to the other negotiator involved here, I think less beset by this manner of thinking, I’ll leave it to her to engage her blog/book issues herself.

Roughly speaking, my schema is to offer you accounts and observations about the world out there which we encounter on our carefully chosen itinerary of barely scratching the world’s surface, even with a year of scratching at our disposal. The inner workings and inter-workings of the three of us – what it is like to travel with two loved ones for a year, and how the many and ongoing encounters with one another and with the offerings and demands of the world we will wend our way through affect and change us as individuals and in our relationships as parents and child, as married people, as individuals positioned differently in the ever-changing arrays of living – these things about us are the stuff and soul of the book. The rub might be obvious: the line, actually lines demarcating what’s out there from what’s in here (the family circle and each of our minds and hearts) is hard to draw, especially as the inside is implicated in the outside, most essentially because both constitute and are filtered through experience, thought, and language. (Taking and posting photos – Sarah’s and Gideon’s domains – are more clear cut.) So, deciding what’s in and out of the blog, because what constitutes the in(side) and the out(side) of the respective worlds we are living and seeking to understand is often indeterminate, is an ongoing and inherently messy and probably shifting process which I am negotiating with that very tough and a bit ambivalent negotiator, myself. As to the other negotiator involved here, I think less beset by this manner of thinking, I’ll leave it to her to engage her blog/book issues herself. Lofoton, above the Arctic Circle in midnight summertime sun Norway, was a spectacular place to begin our journey. The breath-taking and -giving monumental landscapes, which can be imaginatively discerned well enough through the miniaturized photos (which I expect Sarah will happily insert), as a undulating symphony of approachable mountains and hills, and lakes and fjords. We drove for hours through it at nearly every hour of the 24-hour day, including 1 in the morning, 5 in the morning, 9 in the evening, 11 in the evening and the more conventional sightseeing times in-between. Riveted and scanning, still and pointing, quiet and in full conversation (see shadows above), we drove, we walked, we looked, we breathed, we experienced Lofoton. For two days our ordinary rhythms of sleeping and waking, eating and… we cast asunder. We walked (see Gideon, double above), we hiked (straight up a small mountain nearing midnight), we drank coffee outdoors in the just warm enough weather, as we lived according to our own time- and activity-wants. We valiantly twice tried to see the sun at solar midnight descend, bounce, and rise slightly above the horizon, and failed for differently reasons. The attempts felt (in our exaggerating subjectivity) near-heroic, so we, the reasonable agents we are, felt disappointed yet satisfied that we had done our best. And so, we have yet another reason to return to Lofoton, to find and follow the midnight sun.

Lofoton, above the Arctic Circle in midnight summertime sun Norway, was a spectacular place to begin our journey. The breath-taking and -giving monumental landscapes, which can be imaginatively discerned well enough through the miniaturized photos (which I expect Sarah will happily insert), as a undulating symphony of approachable mountains and hills, and lakes and fjords. We drove for hours through it at nearly every hour of the 24-hour day, including 1 in the morning, 5 in the morning, 9 in the evening, 11 in the evening and the more conventional sightseeing times in-between. Riveted and scanning, still and pointing, quiet and in full conversation (see shadows above), we drove, we walked, we looked, we breathed, we experienced Lofoton. For two days our ordinary rhythms of sleeping and waking, eating and… we cast asunder. We walked (see Gideon, double above), we hiked (straight up a small mountain nearing midnight), we drank coffee outdoors in the just warm enough weather, as we lived according to our own time- and activity-wants. We valiantly twice tried to see the sun at solar midnight descend, bounce, and rise slightly above the horizon, and failed for differently reasons. The attempts felt (in our exaggerating subjectivity) near-heroic, so we, the reasonable agents we are, felt disappointed yet satisfied that we had done our best. And so, we have yet another reason to return to Lofoton, to find and follow the midnight sun.