Gideon couldn’t resist the Shake Shack French fries available near gate 35 at JFK as we took off for leg 2 of the great adventure, even though they are not advertised as gluten-free. “I’ve eaten them plenty of times and it’s always been fine.” Danny and I looked at each other, and shrugged.

Several hours into our flight, Gideon confessed he was feeling sick. Then, sicker. He began to insist that I corral the flight attendant, who was in the middle of serving meals, and demand that she allow him to decamp from Economy and take up residence in First Class, because of his condition. He began to sweat. Then he was cold. He feared vomiting. Finally, I did manage to locate three contiguous unoccupied seats at the very back of the plane, approached a flight attendant, who kindly offered to move the backpacks and coats spread out there so that Gideon could lie down and rest.

Half an hour later, I went back to check on him, and Gideon asked me to sit with him. I settled into the aisle seat, and he snuggled his head into my lap. After a few minutes, he said, “Talk to me.”

Danny and Gideon have a default conversational setting. It serves multiple and various functions, depending upon what’s switched it on. Emotional connection. Injury salve, distraction when vials of blood are being drawn from a vein. Exercises in the art of analytical thinking. Strategical inquiry. Information sharing. Passing the time during this or that boring interlude during the day — long drive, waiting in a line. More. That setting could be called GESPN, Goldhagen Entertainment Sports Network. When switched on, GESPN is usually but not always tuned to football, though other sports, basketball, soccer, bicycle racing are also featured.

To extend the metaphor, the only network to which Gideon and I routinely turn might be called GEGAN –Goldhagen Entertainment Goofing Around Network. And in this situation, GEGAN was not appropriate. Flummoxed. I asked, “Do you want me to tell you a story?” Hoping the answer was no.

“Yes.”

For years, I’ve considered myself a rotten storyteller. In college, for an assignment in creative writing I produced a short story, a revenge fantasy about a boyfriend who’d dumped me. My kindly, beloved writing professor, Sears Jayne, whom I would have done nearly anything to please, called me out on it. “It reads like a poison pen note from a jilted lover”, he wrote. Humiliated, I concluded that storytelling would never be my thing, and it never has been. Ask me to tell you a story and my mind becomes empty, a wasteland.

OK Sarah, deliver, I said to myself. Your son is sick.

First I told him a highly elaborated version of the Three Little Pigs which Gideon, surprisingly, had never heard. (What kind of mother was I, anyway, I thought, amused.) It began with Once Upon a Time, ended in the conventional way, and when I’d concluded it, I thought to myself, well, that should convince him that he needs no more stories from me.

“Tell me another,” Gideon said.

Oh, dear. OK, I said, give me a minute. Thinking. That first attempt was framed as a little kid’s story, and he liked it, so let’s stick with that. Images and vignettes flooded my mind until I settled on my childhood in Woodstock, Vermont.

“Once upon I time,” I began, buying myself time. “Once upon a time there was a little girl who had lots and lots of brothers and sisters,” I continued. What next? “Every summer, they lived in a big old house on top of a hill in a little town, where they all argued and played and wrestled and ignored one another, and listened in on each other’s phone conversations.

“The little girl, whose name was Sylvia, was much, much younger than her brothers and sisters. Sylvia was really, really little. And all her brothers and sisters had Big Personalities—one sister was The Brain, one brother was The Rebel, another The Comedian, and so on. They all took up a lot of space, with their Big Personalities. So Sylvia, who was young, often felt very, very small. Sometimes, she felt as though she was invisible.

“Every once in a while, the family’s Daddy would say, ‘How about going to the White Cottage for lunch?’ The White Cottage was a little outdoor diner sitting at the edge of a river, a bit outside of town.

“The White Cottage, the White Cottage!” the children yelled. “Let’s go to the White Cottage!” So they all piled into their Daddy’s light blue convertible with the top down (this was the days before safety and seat belts), and Daddy drove everyone to the White Cottage.

“Once they’d ordered their burgers and fries and milkshakes, one of Sylvia’s brothers turned to her and said, ‘Let’s go down to the river to play until the food comes.’ He took Sylvia by the hand and they scuttered on the dirt down the steep slope to the riverbank together. They took off their socks and sneakers to wade, because it was a very hot day. The Ottaqueechee River was shallow, old, and cool, with lots of soft, smooth rocks lining its bed. Sylvia and her brother waded in until the water came midway up their shins.

“The brother said, ‘Let’s build a house for the fish.’

“Sylvia laughed. ‘Fish don’t live in houses!’

“’They might,’ her brother said. ‘Maybe they do and we just don’t know it. They might just thank us for it.’ Sylvia knew that fish didn’t talk, either. But, since her brother was so much older than her, she began to question what she did and did not know about fish. Together they began gathering up stones.

“At the White Cottage, food always took a very long time to come, so they had time to gather up lots of stones.

“The brother said solemnly, ‘We must make it a big house, because the Ottaqueechee has a lot of fish.’ With great determination, they started constructing the house. ‘Fish houses must be round,’ the brother advised Sylvia. Slowly, they constructed a round wall, about five feet from side to side. ‘The upstream wall should be a lot lower than the downstream wall, so they can get in,’ the brother continued, so they did that too, as they worked.

“As they were finishing, Sylvia heard her father yell, ‘Kids! Food’s here!’ She and her brother stood up. Sylvia noticed that a couple of fish had, indeed, already entered their new home. They seemed happy, swimming around in it. The river flowed on.

“’Bye fish,’ Sylvia said.

“’Bye fish,’ her big brother said.

“The largest of all the fish swam up to the surface, and bobbed its head upwards.

“’Hey!’ The fish said in a loud, strong, voice. ‘Thanks for our house!’

“Sylvia and her brother looked at each other, and laughed. Then they scrambled back up the riverbank, and joined the family to eat lunch.”

Once I finished the story, I looked down at Gideon, who had tears in his eyes. “Is that you and Rog?” he asked.

Yes, I answered. Then he fell asleep.

— Sarah

The exception was Casablanca, but Fez, people tell me, confers this impression with even greater intensity. In its sense of arrested time, Morocco felt very different from other developing societies I’ve encountered. Take India. In India, people’s lives are saturated with tradition, but they do not, or at least did not appear to me to reject modernity. In some of Morocco’s most distant reaches, people seem only dimly aware that modern societies even exist. What are they watching on satellite TV?

The exception was Casablanca, but Fez, people tell me, confers this impression with even greater intensity. In its sense of arrested time, Morocco felt very different from other developing societies I’ve encountered. Take India. In India, people’s lives are saturated with tradition, but they do not, or at least did not appear to me to reject modernity. In some of Morocco’s most distant reaches, people seem only dimly aware that modern societies even exist. What are they watching on satellite TV?

Sometimes, in larger buildings, internal rooms with tiny windows butt up onto rooms opening onto subcourtyards with skylit roofs.

Sometimes, in larger buildings, internal rooms with tiny windows butt up onto rooms opening onto subcourtyards with skylit roofs. Spatial organization, spatial sequences – all are straightforward, even banal. (If the site varies topographically, sometimes there’s a little more action, as in the palace at Telouet.) So the colorful, intricate patterns constitute the only means of arresting our visual interest — or, to invert the formulation, to compensate for the lack of design complexity.

Spatial organization, spatial sequences – all are straightforward, even banal. (If the site varies topographically, sometimes there’s a little more action, as in the palace at Telouet.) So the colorful, intricate patterns constitute the only means of arresting our visual interest — or, to invert the formulation, to compensate for the lack of design complexity. In no place we visited did that differ.

In no place we visited did that differ. and visiting two historic sites, one barely on the beaten track and the other of movie and vernacular architectural fame.

and visiting two historic sites, one barely on the beaten track and the other of movie and vernacular architectural fame.

Sarah, Gideon, and I had an ongoing discussion both about the status of Islamic decoration/craft/art, as whatever its intricacies and pleasing qualities may be, their status as one or the other or the third seems not so obvious, at least to me. A reason I was less enamored with Morocco is that, if its geometric patterning in tile, plaster, and wood is art (which I tend to doubt), then it is art that fails to hold, let alone fascinate, me. Sarah tends to come down on the other side, but I suspect she sort-of agrees with me – Sarah, it’s time to rise to the challenge! Gideon has sided with his Mom but that’s because he sides with himself.

Sarah, Gideon, and I had an ongoing discussion both about the status of Islamic decoration/craft/art, as whatever its intricacies and pleasing qualities may be, their status as one or the other or the third seems not so obvious, at least to me. A reason I was less enamored with Morocco is that, if its geometric patterning in tile, plaster, and wood is art (which I tend to doubt), then it is art that fails to hold, let alone fascinate, me. Sarah tends to come down on the other side, but I suspect she sort-of agrees with me – Sarah, it’s time to rise to the challenge! Gideon has sided with his Mom but that’s because he sides with himself. It is famous as the stage set for films, including most famously Gladiator. We walked in Russell Crowe’s footsteps!!! One merchant (a few structures house tourist-friendly goods) proudly showed us the room in his building where Crowe was imprisoned, and insisted, very good-naturedly, that he and I be photographed there together.

It is famous as the stage set for films, including most famously Gladiator. We walked in Russell Crowe’s footsteps!!! One merchant (a few structures house tourist-friendly goods) proudly showed us the room in his building where Crowe was imprisoned, and insisted, very good-naturedly, that he and I be photographed there together. He told us that he was in the film (among five others) and even the princely sum (which for per-capita-income-challenged Morocco it is) that he received daily for six months for his Gladiatorial film work. I imagined I had remembered him in the film, even though I saw it when it came out twenty years ago. I’ll have to check. The town itself is picturesque and suggestive from afar as it steps us the hill,

He told us that he was in the film (among five others) and even the princely sum (which for per-capita-income-challenged Morocco it is) that he received daily for six months for his Gladiatorial film work. I imagined I had remembered him in the film, even though I saw it when it came out twenty years ago. I’ll have to check. The town itself is picturesque and suggestive from afar as it steps us the hill,

from which it seems to burst forth fully formed and colored in its earthy turrets and more, but far less impressive to walk through which experientially is nothing special. Gideon dubbed it a dud and even Sarah, who sees it as a vernacular Parthenon, admitted performatively after several dozen minutes (“I’m ready to go”) that there’s not much to see there beyond its overall, stunning profile.

from which it seems to burst forth fully formed and colored in its earthy turrets and more, but far less impressive to walk through which experientially is nothing special. Gideon dubbed it a dud and even Sarah, who sees it as a vernacular Parthenon, admitted performatively after several dozen minutes (“I’m ready to go”) that there’s not much to see there beyond its overall, stunning profile. He would have liked to spend several more days in them driving and hiking. They were unexpectedly beautiful, though my need, as our driver, to stay utterly focused on the guardrail-less sliver-thin mountain roads, led me to miss most of it. But the oohs and aahs, and the more evolutionarily advanced modes of expressed-appreciation which Gideon showered us with left the basis for his determination to return to the Atlas unmistakable. Unfortunately for him we had to move on, or, even if we didn’t absolutely have to, we did anyway.

He would have liked to spend several more days in them driving and hiking. They were unexpectedly beautiful, though my need, as our driver, to stay utterly focused on the guardrail-less sliver-thin mountain roads, led me to miss most of it. But the oohs and aahs, and the more evolutionarily advanced modes of expressed-appreciation which Gideon showered us with left the basis for his determination to return to the Atlas unmistakable. Unfortunately for him we had to move on, or, even if we didn’t absolutely have to, we did anyway. We spent nearly two weeks in Morocco, and neither Gideon nor Danny nor I, all of us curious and sociable people, developed the slightest connection to anyone. Not to the taxi drivers or the hotel proprietors, not to the food servers, not to the merchants in the souks,

We spent nearly two weeks in Morocco, and neither Gideon nor Danny nor I, all of us curious and sociable people, developed the slightest connection to anyone. Not to the taxi drivers or the hotel proprietors, not to the food servers, not to the merchants in the souks,

whom we passed on the way home to our homey little riad n

whom we passed on the way home to our homey little riad n

Perhaps it’s just my imagination, but to me, it felt as though two linked dynamics were getting in the way. There’s the apparently inherent tension between modernity and Islamic orthodoxy. And then, there’s education.

Perhaps it’s just my imagination, but to me, it felt as though two linked dynamics were getting in the way. There’s the apparently inherent tension between modernity and Islamic orthodoxy. And then, there’s education.

Do some think, infidel, and silently reprehend me for dressing “immodestly”?

Do some think, infidel, and silently reprehend me for dressing “immodestly”?

Don’t misunderstand: we encountered women everywhere we went. Women in burqas, women in niqabs, women in hijabs (that’s most of them), women wearing cutoff shorts and t-shirts (mainly tourists). The women in burqas and full-length gowns tended to be older. Almost always, they were sitting with one another, off by themselves, occasionally with a son or a child.

Don’t misunderstand: we encountered women everywhere we went. Women in burqas, women in niqabs, women in hijabs (that’s most of them), women wearing cutoff shorts and t-shirts (mainly tourists). The women in burqas and full-length gowns tended to be older. Almost always, they were sitting with one another, off by themselves, occasionally with a son or a child.

In our perambulations we saw husbands walking with wives, not so frequently. Fathers with their families, almost never. In the countryside’s public places we saw practically no women at all.

In our perambulations we saw husbands walking with wives, not so frequently. Fathers with their families, almost never. In the countryside’s public places we saw practically no women at all.

that Gideon and Sarah, immediate enthusiasts, lobbied for staying even longer than the planned week. This was even before we saw our Airbnb riad in the medina, with which they instantly fell in love.

that Gideon and Sarah, immediate enthusiasts, lobbied for staying even longer than the planned week. This was even before we saw our Airbnb riad in the medina, with which they instantly fell in love.

A consistent theme of our time in Morocco was that I liked what we saw and what we did somewhat less well than they did. To what extent this was owing to our different appreciations of the temperature, different temperaments regarding the hustle and hustling of the medina (where we walked with big targets on our fronts and backs), or differential ability to ignore or look beyond the manifestly subordinated place of women, rather than to different judgments about what is interesting or meritorious, is hard to know. Nonetheless, Morocco certainly presented a different face, or many different faces, from what else we had seen in Africa. This alone made it interesting.

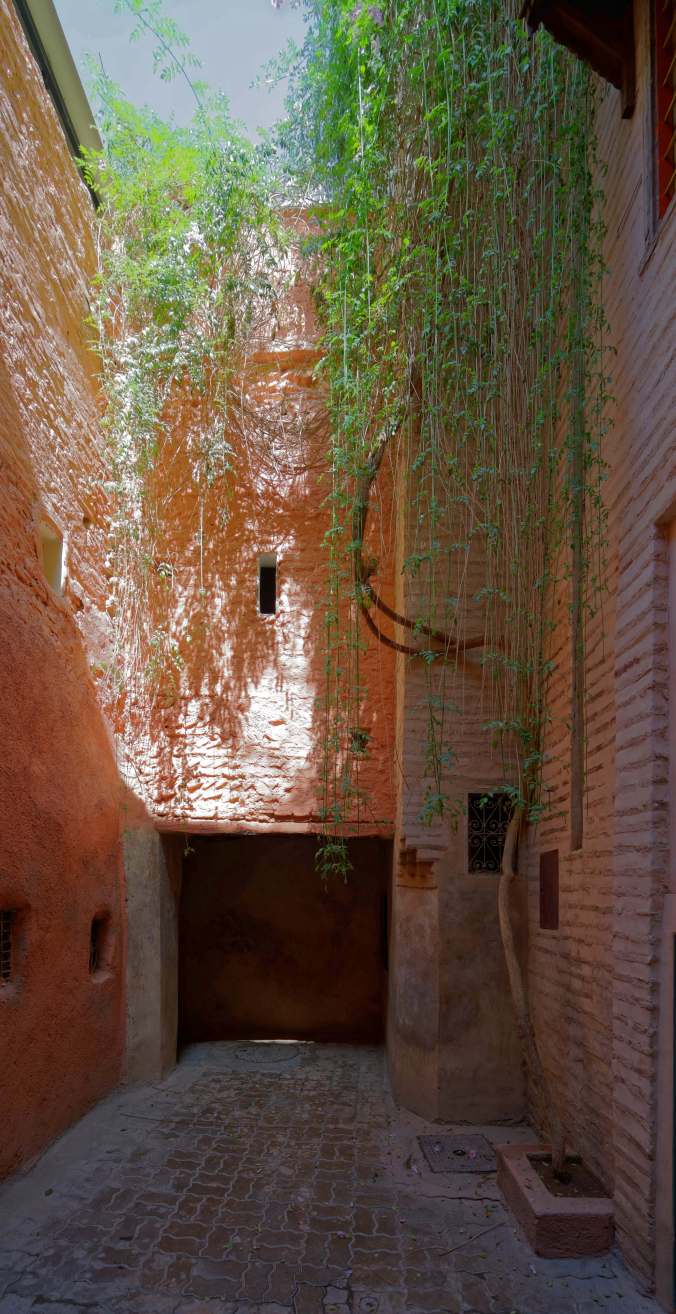

A consistent theme of our time in Morocco was that I liked what we saw and what we did somewhat less well than they did. To what extent this was owing to our different appreciations of the temperature, different temperaments regarding the hustle and hustling of the medina (where we walked with big targets on our fronts and backs), or differential ability to ignore or look beyond the manifestly subordinated place of women, rather than to different judgments about what is interesting or meritorious, is hard to know. Nonetheless, Morocco certainly presented a different face, or many different faces, from what else we had seen in Africa. This alone made it interesting. traversing the narrow alleyways of our residential area to the end of what was a dead end where our entrance lay. Once inside, courtyard open to the sky,

traversing the narrow alleyways of our residential area to the end of what was a dead end where our entrance lay. Once inside, courtyard open to the sky, we were contained in our own mid-century, stoned Moroccan world, except for the five-times daily (the first occurred at 5:45 AM), insistent call to prayers to the various nearby mosques, which loudspeakers made impossible to ignore.

we were contained in our own mid-century, stoned Moroccan world, except for the five-times daily (the first occurred at 5:45 AM), insistent call to prayers to the various nearby mosques, which loudspeakers made impossible to ignore.

Of course, today most of it is oriented to tourists, with on the whole more appealing offerings (rugs, ceramics, silver and beads in all kinds of constellations)

Of course, today most of it is oriented to tourists, with on the whole more appealing offerings (rugs, ceramics, silver and beads in all kinds of constellations) than the norm, but especially where we were, it also provided the lifeline of daily needs for the inhabitants – small grocers, stores with household essentials, laundries, and cafes for the men (singly, paired, in clusters) to while away the day.

than the norm, but especially where we were, it also provided the lifeline of daily needs for the inhabitants – small grocers, stores with household essentials, laundries, and cafes for the men (singly, paired, in clusters) to while away the day.

a garden of desert plants, purchased and rejuvenated by Yves Saint Lauren and his partner Pierre Berge. It is as memorable and spectacular a contained garden as we have seen, a fiesta of specimen planting and display, with cacti of every sort as beautiful and wholesome as even your imagination could want. Marrakesh has its charms and its magical salmony-colored quality, rendering it, together with its impressively massive walls and the medina they enclose, a city of distinction, and worth visiting. It’s historic and contemporary marquee attractions – including palaces and tombs, museums and villas – are however mainly underwhelming.

a garden of desert plants, purchased and rejuvenated by Yves Saint Lauren and his partner Pierre Berge. It is as memorable and spectacular a contained garden as we have seen, a fiesta of specimen planting and display, with cacti of every sort as beautiful and wholesome as even your imagination could want. Marrakesh has its charms and its magical salmony-colored quality, rendering it, together with its impressively massive walls and the medina they enclose, a city of distinction, and worth visiting. It’s historic and contemporary marquee attractions – including palaces and tombs, museums and villas – are however mainly underwhelming. But the Jardin Marjorelle… the magical Jardin Marjorelle…

But the Jardin Marjorelle… the magical Jardin Marjorelle… The stunning and varied non-Namib landscapes, especially between Sesriem and Walvis Bay, which Sarah described moving through — having over the last few months experienced a range of unforgettable scenic road trips — as one of the best drives ever.

The stunning and varied non-Namib landscapes, especially between Sesriem and Walvis Bay, which Sarah described moving through — having over the last few months experienced a range of unforgettable scenic road trips — as one of the best drives ever. The idiosyncratic hotels we stayed in in the desert, the first being an expensive contemporary castle (at least in wannabe form)

The idiosyncratic hotels we stayed in in the desert, the first being an expensive contemporary castle (at least in wannabe form)  and the second being an inexpensive “desert farm” with as beautiful a desert garden as you could want.

and the second being an inexpensive “desert farm” with as beautiful a desert garden as you could want.

The sunrises.

The sunrises.  The walk from the castle hotel just out there into the desert, with the sense that we could have gone on forever (or until we died of thirst).

The walk from the castle hotel just out there into the desert, with the sense that we could have gone on forever (or until we died of thirst).  The totally (–>this is no hyperbole) unexpected excellent coffee shop and bakery in aptly named Solitude (it’s a few structures strong) — started fifteen years ago by a man who fled his broken life, started anew in this middle-of-nowhere, and, loving it, never left. The lovely small book store in Swakopmund, with books in three sections, one for German, one for Afrikaans (probably, the lingua franca of Namibia), and one for English, and containing an impressive multilingual section on Namibia with many books on the colonial period and the genocide. The good-naturedness and easy-goingness of all the people we met.

The totally (–>this is no hyperbole) unexpected excellent coffee shop and bakery in aptly named Solitude (it’s a few structures strong) — started fifteen years ago by a man who fled his broken life, started anew in this middle-of-nowhere, and, loving it, never left. The lovely small book store in Swakopmund, with books in three sections, one for German, one for Afrikaans (probably, the lingua franca of Namibia), and one for English, and containing an impressive multilingual section on Namibia with many books on the colonial period and the genocide. The good-naturedness and easy-goingness of all the people we met.  The personalized, memorable short week we spent there made Namibia (for the supertough raters) a nine and (for the simply experientially-tuned) a flat out ten.

The personalized, memorable short week we spent there made Namibia (for the supertough raters) a nine and (for the simply experientially-tuned) a flat out ten. Only one paved (in local argot, sealed) highway, admittedly with arterial branches, stretches from north to south; a second, west-east, connects the adjacent towns of Walvis Bay and Swakopmund on the Atlantic with Windhoek. This one runs through the most economically developed regions of the country. Mostly, mines: diamond mines, copper mines, tungsten mines, and two of the top-ten uranium mines in the world.

Only one paved (in local argot, sealed) highway, admittedly with arterial branches, stretches from north to south; a second, west-east, connects the adjacent towns of Walvis Bay and Swakopmund on the Atlantic with Windhoek. This one runs through the most economically developed regions of the country. Mostly, mines: diamond mines, copper mines, tungsten mines, and two of the top-ten uranium mines in the world. The wide, long, rattling journey from Sossusvlei to Swakopmund will surely always be one of most beautiful drives I have ever had the good fortune to enjoy. It’s not spectacular, like the drive from the San Francisco Bay Area up to Sea Ranch on the Pacific Coast, or the drive from Geneva to Lausanne. You really have to watch. I passed the hours gazing out onto these often flat, sometimes rolling expanses of land, parsing out how the sense of deep space came mostly from variations in color saturation, hue, and temperature,

The wide, long, rattling journey from Sossusvlei to Swakopmund will surely always be one of most beautiful drives I have ever had the good fortune to enjoy. It’s not spectacular, like the drive from the San Francisco Bay Area up to Sea Ranch on the Pacific Coast, or the drive from Geneva to Lausanne. You really have to watch. I passed the hours gazing out onto these often flat, sometimes rolling expanses of land, parsing out how the sense of deep space came mostly from variations in color saturation, hue, and temperature,  and noticing subtle shifts in the layered bands of browns, grays, thin, struggling greens.

and noticing subtle shifts in the layered bands of browns, grays, thin, struggling greens.  When the arid ground shifted from flat and sandy to inclined and rockier, my heart leapt, delighting in the textural variation.

When the arid ground shifted from flat and sandy to inclined and rockier, my heart leapt, delighting in the textural variation. Nothing, nothing, nothing. Until you realize that nothing is something. Burrow into these muted colors and thin layers, into this topography. This landscape settles inside you, then stays.

Nothing, nothing, nothing. Until you realize that nothing is something. Burrow into these muted colors and thin layers, into this topography. This landscape settles inside you, then stays. Paved streets. A new shopping mall under construction, outside of town. Two-story concrete frame buildings – nearly everything is concrete frame, not steel– housing the warehouses and offices of various local companies.

Paved streets. A new shopping mall under construction, outside of town. Two-story concrete frame buildings – nearly everything is concrete frame, not steel– housing the warehouses and offices of various local companies.

At the edge of the commercial area, near the shore, sits a little enclosed complex with an arcaded courtyard and a charming lookout tower; once, it housed a boarding school.

At the edge of the commercial area, near the shore, sits a little enclosed complex with an arcaded courtyard and a charming lookout tower; once, it housed a boarding school.

To locals, this place, like the graciously-planted, serpentine beachside pathways, was just another instance of tidy Swakopmund’s gracious provision of landscaping and street furniture.

To locals, this place, like the graciously-planted, serpentine beachside pathways, was just another instance of tidy Swakopmund’s gracious provision of landscaping and street furniture.

In it was an excellent new-and-antiquarian bookstore, filled with German-speaking latte-drinkers and German-language paperbacks.

In it was an excellent new-and-antiquarian bookstore, filled with German-speaking latte-drinkers and German-language paperbacks.  We poked around for a good half hour, turning up a battered Herero-German dictionary, published in 1904.

We poked around for a good half hour, turning up a battered Herero-German dictionary, published in 1904.

We gazed upon them. We walked past and around them. We climbed them. We (Gideon and Sarah) stood astride them and surveyed the dominion. Gideon lay on them. He even, unsuccessfully, tried to roll down them, only to discover that they enveloped and captured his body as they had his imagination and soul.

We gazed upon them. We walked past and around them. We climbed them. We (Gideon and Sarah) stood astride them and surveyed the dominion. Gideon lay on them. He even, unsuccessfully, tried to roll down them, only to discover that they enveloped and captured his body as they had his imagination and soul.

reassembling at our SUV, driving further into the dunescape, taking a four-wheel drive sand-ferry for four kilometers, and trekking afoot twenty minutes deeper up into the dunes, we came upon the nearly sacralized desert landscape, foremost among desert moments in the world, of Deadvlei — to wander among, behold, and contemplate, and, in Sarah’s and my case, talk about the dune-flanked and framed magnificent salt pan

reassembling at our SUV, driving further into the dunescape, taking a four-wheel drive sand-ferry for four kilometers, and trekking afoot twenty minutes deeper up into the dunes, we came upon the nearly sacralized desert landscape, foremost among desert moments in the world, of Deadvlei — to wander among, behold, and contemplate, and, in Sarah’s and my case, talk about the dune-flanked and framed magnificent salt pan

and anything, which was plenty, that the embodied mind of being there conjured up for the hour or so that we basked in this and our singularity, and in our commonality of sharing this place and our lives.

and anything, which was plenty, that the embodied mind of being there conjured up for the hour or so that we basked in this and our singularity, and in our commonality of sharing this place and our lives.

There is a blood-spattered monument in the center of town commemorating the German soldiers that died during the exterminationist slaughter, listing the battles of their heroism. And, reminiscent of the many German firms that were “founded” in the late thirties when their owners bought Jewish-owned firms for a song, many of the Swakopmundian German colonial-era buildings, especially the once-institutional ones, proudly announce the year of their construction, with 1906 and 1907 being prominent numerals. When the Germans finally solved their “Herero Problem” mainly in 1904-05 by slaughtering them, Germans could finally feel comfortable to invest and develop their colonial jewel. Sarah, I gather will be writing more about Swakopmund, which, by the way, was dominated tourist-wise by Germans during our visit. There’s no reason that Germans shouldn’t visit, and Germans — with vacation-time, resources, and curiosity in abundance — are champion travelers in general, so their visibility in Namibia, a former German colony, should not be remarkable. (On the other hand, it was a century ago.) Yet their overwhelming presence made me, attuned to these matters as I am, wonder: How much do they know? And (with this question, I don’t mean to imply approval of any kind), what do they think?

There is a blood-spattered monument in the center of town commemorating the German soldiers that died during the exterminationist slaughter, listing the battles of their heroism. And, reminiscent of the many German firms that were “founded” in the late thirties when their owners bought Jewish-owned firms for a song, many of the Swakopmundian German colonial-era buildings, especially the once-institutional ones, proudly announce the year of their construction, with 1906 and 1907 being prominent numerals. When the Germans finally solved their “Herero Problem” mainly in 1904-05 by slaughtering them, Germans could finally feel comfortable to invest and develop their colonial jewel. Sarah, I gather will be writing more about Swakopmund, which, by the way, was dominated tourist-wise by Germans during our visit. There’s no reason that Germans shouldn’t visit, and Germans — with vacation-time, resources, and curiosity in abundance — are champion travelers in general, so their visibility in Namibia, a former German colony, should not be remarkable. (On the other hand, it was a century ago.) Yet their overwhelming presence made me, attuned to these matters as I am, wonder: How much do they know? And (with this question, I don’t mean to imply approval of any kind), what do they think?