In Auckland, in Queenstown, and most dramatically, in Christchurch, one’s overwhelming impression of NZ is new, new, new. Partly that’s because of the ever-flourishing greenery (Christchurch calls itself “the green city”), yet many other factors contribute to the country’s perpetual sense of freshness. Owing to its isolation –a bunch of islands seemingly floating around in the Pacific – this was one of the last terrains that humans settled, with Pacific Islanders arriving sometime between the 11th and the 13th centuries CE. Since the Maori lived in tribal settlements in wood and thatch, which they rebuilt over and over, the country’s oldest surviving buildings, as far as I can tell, are a handful of dwellings by British colonists from the 1840s onward.

William’s Cottage, now an art gallery, in Queenstown (1864) — note oval bronze plaque to left of front door

Many if not most landmarks date to the early 20th century, including (surprise!) a sumptuous little Carnegie Library in Hokitika on the west coast, which we stumbled upon en route to Christchurch, driving up the South Island’s west coast.

Carnegie Library (1902), Hokitika, now the Hokitika Museum

Despite, or perhaps because of these comparatively slender historical pickings, everywhere we went, we were struck by the determined celebration of local history. (Having spent my 20s with my head, arms, and mind buried in archives, it occurred to me that the availability of records, and the manageability of their number, surely helps facilitate this apparent preoccupation with history — NZ’s land area measures around the size of Great Britain, while its peoples number fewer than five million, which is one-fifth the population of New York City’s metropolitan area). Wherever we went, we frequently found ourselves standing in front of bronze plaques and laminated wood signs, telling tales of the explorer who first navigated this or that fiord, who first huddled into this spit of land, accompanied by his herd of sheep; of the colonist who planted this or that specimen tree, died here, did that.

Also, references to and artifacts of Maori culture pervade linguistic and visual culture, appearing in place names and dual-language signs; celebrated in museums, alluded to in decorative patterns on printed clothing, jade jewelry, statues, stenciled wallpaper.  The Maori people were never very numerous on these islands; currently, they account for three per cent of the country’s population. Such gestures go part way to redress past wrongs to these indigenous people, to be sure, but I suspect it and all these other historical markers serve a larger function: that of constructing a robust narrative of NZ nationhood and identity.

The Maori people were never very numerous on these islands; currently, they account for three per cent of the country’s population. Such gestures go part way to redress past wrongs to these indigenous people, to be sure, but I suspect it and all these other historical markers serve a larger function: that of constructing a robust narrative of NZ nationhood and identity.

Even with these historical markers, in cities, the impression is that you are immersed in the recent or the now, and Christchurch, a city of 240,000 on the east coast of the South Island, is the newest of all this new. In 2011, “the shakes” – a 6.3 earthquake – devastated the central area of the city, severely damaging its large cathedral (built between 1864 and 1904), as well as many other historic buildings.

Rebuilding a small church downtown

95% of the buildings in the central business district were either destroyed in the earthquake itself, or declared unsafe, and subsequently demolished.

Yup, that’s adjacent to the Central Business District

In residential areas, of the 100,000 homes damaged, approximately 10,000 had to be demolished.

Built environmental junkie types will know Christchurch from Shigeru Ban’s gorgeous, inspiring Transitional Cathedral, aka Cardboard Cathedral, which stands in as the seat for the Anglican ministry, as Christchurch’s old, heavily damaged Cathedral continues its embattled way toward reconstruction.

Entrance, Shigeru Ban’s Transitional Cathedral

The first major building completed after the earthquake, Ban’s TC was constructed largely of recyclable and/or inexpensive materials: huge cardboard tubes comprise the nave’s vaults; translucent, polycarbonate for the roof;

The four rectangular rooms with windows are recycled shipping containers

disused shipping containers serve as the ministry offices. The slight curve of the roof off-axis (the shape is not a perfect triangle),  which creates a subtle, compelling dynamism in the nave,

which creates a subtle, compelling dynamism in the nave,

matched the bubbly personality of Hilde, a sweet, lively woman who welcomed us by proudly revealing that she was “in her tenth decade”, before she told us, quite informatively, about the city, the church, and her congregation.

All in all, in Christchurch you get to see something both rare and thought-provoking. If you were to build the best city you could ex novo, what would you do? Other such experiments exist. In the past: Brasilia, New Delhi, Chandigarh. Today: Masdar in Abu Dhabi by Foster and Partners, and countless new cities in China, but the former remains largely unexecuted, and the latter exercises are so vast in scale that speed of execution and developer profits were systematically privileged over sophistication in design.

Christchurch may be different. It’s too early to tell for sure. Much of downtown remains a vast construction site littered with empty plots of land, monuments to the city’s ravaged state. But even the way the city has approached those voids is impressive. To keep people’s spirits up amidst all those vacant lots, public art has been installed.

Glulam arches make a pathway downtown

The brightly colored animals resemble the sheep, for which NZ is justly famous

And there are murals, along with informal installations, too.

Mural to the left, temporary stage for impromptu performances at right

Building has proceeded slowly in the Central Business District — Christchurchians grumble about it, then shrug, adding, it’s a great city. The CBD has been divided into precincts for retail, “innovation” (which I gather means hi-tech), health, performing and visual arts, and “justice and emergency services”. Dozens of large new buildings are under construction: a new metro sports facility, a new central library, a new convention center. A new transit and bus station opened recently.

Building has proceeded slowly in the Central Business District — Christchurchians grumble about it, then shrug, adding, it’s a great city. The CBD has been divided into precincts for retail, “innovation” (which I gather means hi-tech), health, performing and visual arts, and “justice and emergency services”. Dozens of large new buildings are under construction: a new metro sports facility, a new central library, a new convention center. A new transit and bus station opened recently.

New park under construction, with Ban’s Transitional Cathedral to the left

Large green strips of new parkland and green plazas solves one of the central problems of rebuilding; namely, so much less office space is now needed downtown because of people’s increasingly mobile work practices.

If the residential areas are any indication, the results promise to be both instructive and impressive. Christchurchians needed to build homes quickly, so residential development has outpaced commercial and governmental projects. Our Air BnB, called the Little Black Hut, served as a temporary residence for husband-and-wife real estate developers, who had lost their own home during the shakes. Vertical wood siding, stained black, encircles the exterior, and white-stained plywood sheets line its interiors.

Little Black Hut, Christchurch: A place to stay

A couple of days of walking around the city suggested that the Little Black Hut’s design finesse was not unusual: most homes are small, but the detailing and compositional sensibility even in little cinder block, wood, or corrugated-metal-sided homes looks pretty well done.

A couple of days of walking around the city suggested that the Little Black Hut’s design finesse was not unusual: most homes are small, but the detailing and compositional sensibility even in little cinder block, wood, or corrugated-metal-sided homes looks pretty well done.

How little we missed the “sense of history” so prized amongst Americans! Running into the few remaining Victorian houses, grand and modest, provided enjoyment but not the sense of relief one finds when stumbling upon even modest historic structures in the United States. What we found in Christchurch substantiates the argument I advanced in WtYW that the problem in the US built environment is less old (better)-versus-new (clueless), but the poor design quality and craftsmanship of new construction. In Christchurch, high quality new homes, commercial, and retail buildings could be found everywhere. Even the mediocre buildings are good.

How little we missed the “sense of history” so prized amongst Americans! Running into the few remaining Victorian houses, grand and modest, provided enjoyment but not the sense of relief one finds when stumbling upon even modest historic structures in the United States. What we found in Christchurch substantiates the argument I advanced in WtYW that the problem in the US built environment is less old (better)-versus-new (clueless), but the poor design quality and craftsmanship of new construction. In Christchurch, high quality new homes, commercial, and retail buildings could be found everywhere. Even the mediocre buildings are good.  Stay tuned, then, for the new iteration of New Zealand’s garden city — and dream.

Stay tuned, then, for the new iteration of New Zealand’s garden city — and dream.

— Sarah

and here’s the sunrise that greeted us in the morning.

and here’s the sunrise that greeted us in the morning.

seeing those mountains shooting straight out of its deep, black waters is unforgettable.

seeing those mountains shooting straight out of its deep, black waters is unforgettable.

An army of eateries, several divisions of sleeperies,

An army of eateries, several divisions of sleeperies,

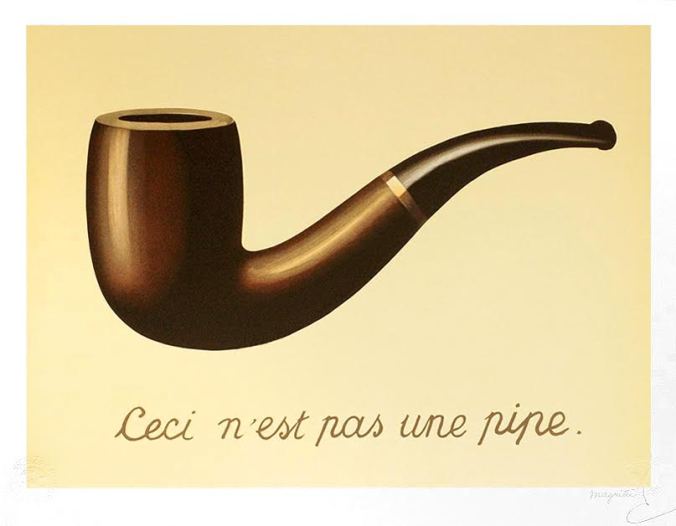

Before pursuing this line, I admit that I recoil a bit from being labeled a tourist, as, whatever its original sense, today it sounds so unserious and connotes at least partly negatively, and I like to buoy my spirits with the mental placebo that what we (Sarah and I, and Sarah, Gideon, and I) should not be clothed in this appellation.

Before pursuing this line, I admit that I recoil a bit from being labeled a tourist, as, whatever its original sense, today it sounds so unserious and connotes at least partly negatively, and I like to buoy my spirits with the mental placebo that what we (Sarah and I, and Sarah, Gideon, and I) should not be clothed in this appellation.

Much of what we do when we visit places relates to our, especially Sarah’s, professional work, and this journey is intended to produce at least a couple of books, so my own perhaps at least partly self-deceptive self-conception as anything but an authenticity-sullying tourist is buttressed and legitimized by our vocational bents and activities. We are at once anthropologists of the globalized world, sociologists of the built and unbuilt environment, social psychologists of family life, and cultural critics of the arts and gluten-free food. Alas, to the untrained eye, we look and sound like tourists. The diagnostic truism “If it looks like a duck, and sounds like a duck…” is either on the money or, like many truisms, not clever enough by half.

Much of what we do when we visit places relates to our, especially Sarah’s, professional work, and this journey is intended to produce at least a couple of books, so my own perhaps at least partly self-deceptive self-conception as anything but an authenticity-sullying tourist is buttressed and legitimized by our vocational bents and activities. We are at once anthropologists of the globalized world, sociologists of the built and unbuilt environment, social psychologists of family life, and cultural critics of the arts and gluten-free food. Alas, to the untrained eye, we look and sound like tourists. The diagnostic truism “If it looks like a duck, and sounds like a duck…” is either on the money or, like many truisms, not clever enough by half. Thus, we call the people at Stowe or Alta “skiers”. The problem with naming the visitors to Queenstown is that we have no linguistic concept that captures what they are, and so we are stuck with choosing between the anodyne “visitors” and the iodine “tourists”.

Thus, we call the people at Stowe or Alta “skiers”. The problem with naming the visitors to Queenstown is that we have no linguistic concept that captures what they are, and so we are stuck with choosing between the anodyne “visitors” and the iodine “tourists”. The exception was Casablanca, but Fez, people tell me, confers this impression with even greater intensity. In its sense of arrested time, Morocco felt very different from other developing societies I’ve encountered. Take India. In India, people’s lives are saturated with tradition, but they do not, or at least did not appear to me to reject modernity. In some of Morocco’s most distant reaches, people seem only dimly aware that modern societies even exist. What are they watching on satellite TV?

The exception was Casablanca, but Fez, people tell me, confers this impression with even greater intensity. In its sense of arrested time, Morocco felt very different from other developing societies I’ve encountered. Take India. In India, people’s lives are saturated with tradition, but they do not, or at least did not appear to me to reject modernity. In some of Morocco’s most distant reaches, people seem only dimly aware that modern societies even exist. What are they watching on satellite TV?

Sometimes, in larger buildings, internal rooms with tiny windows butt up onto rooms opening onto subcourtyards with skylit roofs.

Sometimes, in larger buildings, internal rooms with tiny windows butt up onto rooms opening onto subcourtyards with skylit roofs. Spatial organization, spatial sequences – all are straightforward, even banal. (If the site varies topographically, sometimes there’s a little more action, as in the palace at Telouet.) So the colorful, intricate patterns constitute the only means of arresting our visual interest — or, to invert the formulation, to compensate for the lack of design complexity.

Spatial organization, spatial sequences – all are straightforward, even banal. (If the site varies topographically, sometimes there’s a little more action, as in the palace at Telouet.) So the colorful, intricate patterns constitute the only means of arresting our visual interest — or, to invert the formulation, to compensate for the lack of design complexity. In no place we visited did that differ.

In no place we visited did that differ.

that Gideon and Sarah, immediate enthusiasts, lobbied for staying even longer than the planned week. This was even before we saw our Airbnb riad in the medina, with which they instantly fell in love.

that Gideon and Sarah, immediate enthusiasts, lobbied for staying even longer than the planned week. This was even before we saw our Airbnb riad in the medina, with which they instantly fell in love.

A consistent theme of our time in Morocco was that I liked what we saw and what we did somewhat less well than they did. To what extent this was owing to our different appreciations of the temperature, different temperaments regarding the hustle and hustling of the medina (where we walked with big targets on our fronts and backs), or differential ability to ignore or look beyond the manifestly subordinated place of women, rather than to different judgments about what is interesting or meritorious, is hard to know. Nonetheless, Morocco certainly presented a different face, or many different faces, from what else we had seen in Africa. This alone made it interesting.

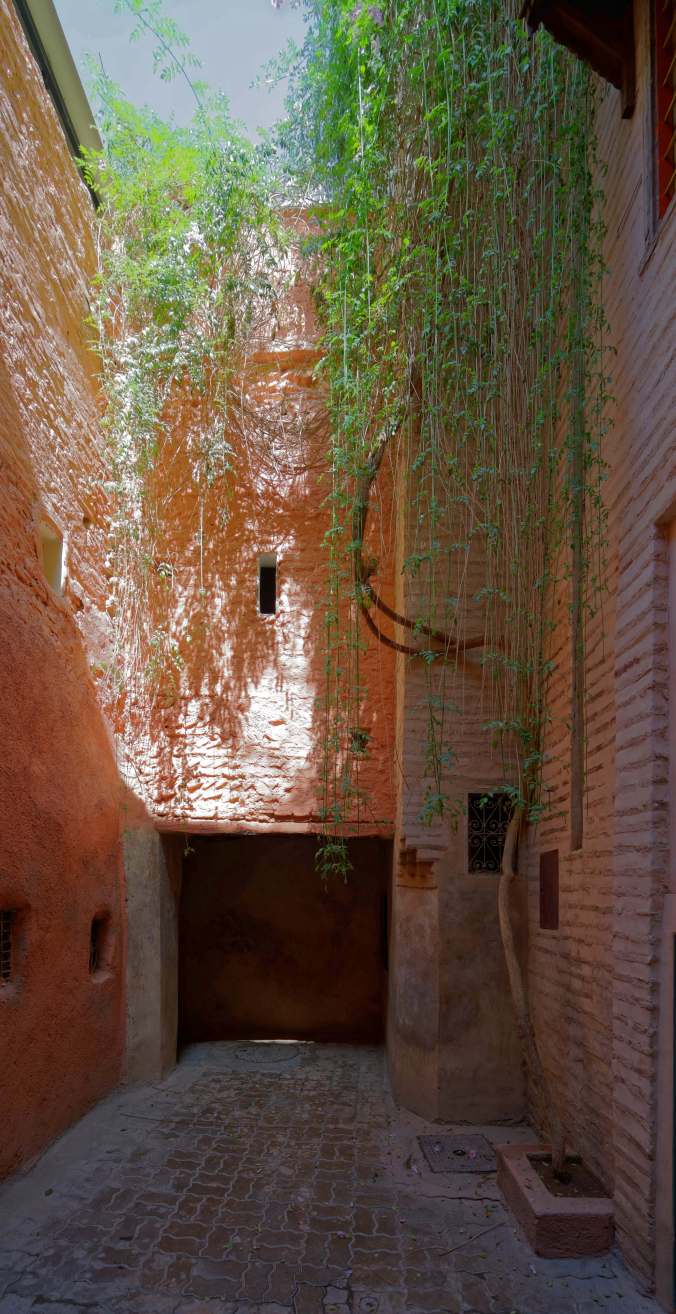

A consistent theme of our time in Morocco was that I liked what we saw and what we did somewhat less well than they did. To what extent this was owing to our different appreciations of the temperature, different temperaments regarding the hustle and hustling of the medina (where we walked with big targets on our fronts and backs), or differential ability to ignore or look beyond the manifestly subordinated place of women, rather than to different judgments about what is interesting or meritorious, is hard to know. Nonetheless, Morocco certainly presented a different face, or many different faces, from what else we had seen in Africa. This alone made it interesting. traversing the narrow alleyways of our residential area to the end of what was a dead end where our entrance lay. Once inside, courtyard open to the sky,

traversing the narrow alleyways of our residential area to the end of what was a dead end where our entrance lay. Once inside, courtyard open to the sky, we were contained in our own mid-century, stoned Moroccan world, except for the five-times daily (the first occurred at 5:45 AM), insistent call to prayers to the various nearby mosques, which loudspeakers made impossible to ignore.

we were contained in our own mid-century, stoned Moroccan world, except for the five-times daily (the first occurred at 5:45 AM), insistent call to prayers to the various nearby mosques, which loudspeakers made impossible to ignore.

Of course, today most of it is oriented to tourists, with on the whole more appealing offerings (rugs, ceramics, silver and beads in all kinds of constellations)

Of course, today most of it is oriented to tourists, with on the whole more appealing offerings (rugs, ceramics, silver and beads in all kinds of constellations) than the norm, but especially where we were, it also provided the lifeline of daily needs for the inhabitants – small grocers, stores with household essentials, laundries, and cafes for the men (singly, paired, in clusters) to while away the day.

than the norm, but especially where we were, it also provided the lifeline of daily needs for the inhabitants – small grocers, stores with household essentials, laundries, and cafes for the men (singly, paired, in clusters) to while away the day.

a garden of desert plants, purchased and rejuvenated by Yves Saint Lauren and his partner Pierre Berge. It is as memorable and spectacular a contained garden as we have seen, a fiesta of specimen planting and display, with cacti of every sort as beautiful and wholesome as even your imagination could want. Marrakesh has its charms and its magical salmony-colored quality, rendering it, together with its impressively massive walls and the medina they enclose, a city of distinction, and worth visiting. It’s historic and contemporary marquee attractions – including palaces and tombs, museums and villas – are however mainly underwhelming.

a garden of desert plants, purchased and rejuvenated by Yves Saint Lauren and his partner Pierre Berge. It is as memorable and spectacular a contained garden as we have seen, a fiesta of specimen planting and display, with cacti of every sort as beautiful and wholesome as even your imagination could want. Marrakesh has its charms and its magical salmony-colored quality, rendering it, together with its impressively massive walls and the medina they enclose, a city of distinction, and worth visiting. It’s historic and contemporary marquee attractions – including palaces and tombs, museums and villas – are however mainly underwhelming. But the Jardin Marjorelle… the magical Jardin Marjorelle…

But the Jardin Marjorelle… the magical Jardin Marjorelle… The stunning and varied non-Namib landscapes, especially between Sesriem and Walvis Bay, which Sarah described moving through — having over the last few months experienced a range of unforgettable scenic road trips — as one of the best drives ever.

The stunning and varied non-Namib landscapes, especially between Sesriem and Walvis Bay, which Sarah described moving through — having over the last few months experienced a range of unforgettable scenic road trips — as one of the best drives ever. The idiosyncratic hotels we stayed in in the desert, the first being an expensive contemporary castle (at least in wannabe form)

The idiosyncratic hotels we stayed in in the desert, the first being an expensive contemporary castle (at least in wannabe form)  and the second being an inexpensive “desert farm” with as beautiful a desert garden as you could want.

and the second being an inexpensive “desert farm” with as beautiful a desert garden as you could want.

The sunrises.

The sunrises.  The walk from the castle hotel just out there into the desert, with the sense that we could have gone on forever (or until we died of thirst).

The walk from the castle hotel just out there into the desert, with the sense that we could have gone on forever (or until we died of thirst).  The totally (–>this is no hyperbole) unexpected excellent coffee shop and bakery in aptly named Solitude (it’s a few structures strong) — started fifteen years ago by a man who fled his broken life, started anew in this middle-of-nowhere, and, loving it, never left. The lovely small book store in Swakopmund, with books in three sections, one for German, one for Afrikaans (probably, the lingua franca of Namibia), and one for English, and containing an impressive multilingual section on Namibia with many books on the colonial period and the genocide. The good-naturedness and easy-goingness of all the people we met.

The totally (–>this is no hyperbole) unexpected excellent coffee shop and bakery in aptly named Solitude (it’s a few structures strong) — started fifteen years ago by a man who fled his broken life, started anew in this middle-of-nowhere, and, loving it, never left. The lovely small book store in Swakopmund, with books in three sections, one for German, one for Afrikaans (probably, the lingua franca of Namibia), and one for English, and containing an impressive multilingual section on Namibia with many books on the colonial period and the genocide. The good-naturedness and easy-goingness of all the people we met.  The personalized, memorable short week we spent there made Namibia (for the supertough raters) a nine and (for the simply experientially-tuned) a flat out ten.

The personalized, memorable short week we spent there made Namibia (for the supertough raters) a nine and (for the simply experientially-tuned) a flat out ten. Only one paved (in local argot, sealed) highway, admittedly with arterial branches, stretches from north to south; a second, west-east, connects the adjacent towns of Walvis Bay and Swakopmund on the Atlantic with Windhoek. This one runs through the most economically developed regions of the country. Mostly, mines: diamond mines, copper mines, tungsten mines, and two of the top-ten uranium mines in the world.

Only one paved (in local argot, sealed) highway, admittedly with arterial branches, stretches from north to south; a second, west-east, connects the adjacent towns of Walvis Bay and Swakopmund on the Atlantic with Windhoek. This one runs through the most economically developed regions of the country. Mostly, mines: diamond mines, copper mines, tungsten mines, and two of the top-ten uranium mines in the world. The wide, long, rattling journey from Sossusvlei to Swakopmund will surely always be one of most beautiful drives I have ever had the good fortune to enjoy. It’s not spectacular, like the drive from the San Francisco Bay Area up to Sea Ranch on the Pacific Coast, or the drive from Geneva to Lausanne. You really have to watch. I passed the hours gazing out onto these often flat, sometimes rolling expanses of land, parsing out how the sense of deep space came mostly from variations in color saturation, hue, and temperature,

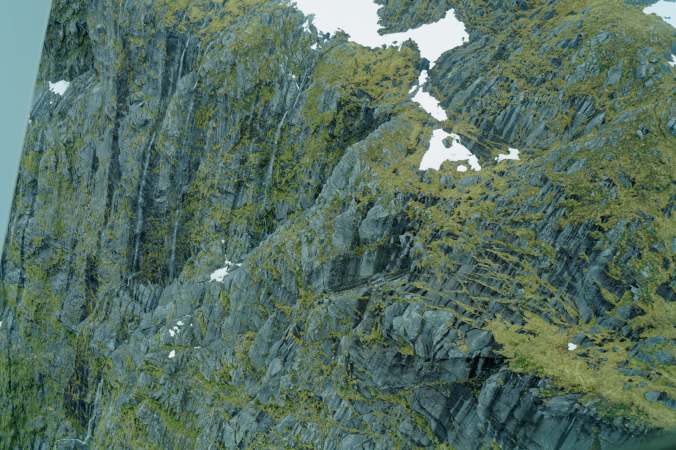

The wide, long, rattling journey from Sossusvlei to Swakopmund will surely always be one of most beautiful drives I have ever had the good fortune to enjoy. It’s not spectacular, like the drive from the San Francisco Bay Area up to Sea Ranch on the Pacific Coast, or the drive from Geneva to Lausanne. You really have to watch. I passed the hours gazing out onto these often flat, sometimes rolling expanses of land, parsing out how the sense of deep space came mostly from variations in color saturation, hue, and temperature,  and noticing subtle shifts in the layered bands of browns, grays, thin, struggling greens.

and noticing subtle shifts in the layered bands of browns, grays, thin, struggling greens.  When the arid ground shifted from flat and sandy to inclined and rockier, my heart leapt, delighting in the textural variation.

When the arid ground shifted from flat and sandy to inclined and rockier, my heart leapt, delighting in the textural variation. Nothing, nothing, nothing. Until you realize that nothing is something. Burrow into these muted colors and thin layers, into this topography. This landscape settles inside you, then stays.

Nothing, nothing, nothing. Until you realize that nothing is something. Burrow into these muted colors and thin layers, into this topography. This landscape settles inside you, then stays. Paved streets. A new shopping mall under construction, outside of town. Two-story concrete frame buildings – nearly everything is concrete frame, not steel– housing the warehouses and offices of various local companies.

Paved streets. A new shopping mall under construction, outside of town. Two-story concrete frame buildings – nearly everything is concrete frame, not steel– housing the warehouses and offices of various local companies.

At the edge of the commercial area, near the shore, sits a little enclosed complex with an arcaded courtyard and a charming lookout tower; once, it housed a boarding school.

At the edge of the commercial area, near the shore, sits a little enclosed complex with an arcaded courtyard and a charming lookout tower; once, it housed a boarding school.

To locals, this place, like the graciously-planted, serpentine beachside pathways, was just another instance of tidy Swakopmund’s gracious provision of landscaping and street furniture.

To locals, this place, like the graciously-planted, serpentine beachside pathways, was just another instance of tidy Swakopmund’s gracious provision of landscaping and street furniture.

In it was an excellent new-and-antiquarian bookstore, filled with German-speaking latte-drinkers and German-language paperbacks.

In it was an excellent new-and-antiquarian bookstore, filled with German-speaking latte-drinkers and German-language paperbacks.  We poked around for a good half hour, turning up a battered Herero-German dictionary, published in 1904.

We poked around for a good half hour, turning up a battered Herero-German dictionary, published in 1904.

We gazed upon them. We walked past and around them. We climbed them. We (Gideon and Sarah) stood astride them and surveyed the dominion. Gideon lay on them. He even, unsuccessfully, tried to roll down them, only to discover that they enveloped and captured his body as they had his imagination and soul.

We gazed upon them. We walked past and around them. We climbed them. We (Gideon and Sarah) stood astride them and surveyed the dominion. Gideon lay on them. He even, unsuccessfully, tried to roll down them, only to discover that they enveloped and captured his body as they had his imagination and soul.

reassembling at our SUV, driving further into the dunescape, taking a four-wheel drive sand-ferry for four kilometers, and trekking afoot twenty minutes deeper up into the dunes, we came upon the nearly sacralized desert landscape, foremost among desert moments in the world, of Deadvlei — to wander among, behold, and contemplate, and, in Sarah’s and my case, talk about the dune-flanked and framed magnificent salt pan

reassembling at our SUV, driving further into the dunescape, taking a four-wheel drive sand-ferry for four kilometers, and trekking afoot twenty minutes deeper up into the dunes, we came upon the nearly sacralized desert landscape, foremost among desert moments in the world, of Deadvlei — to wander among, behold, and contemplate, and, in Sarah’s and my case, talk about the dune-flanked and framed magnificent salt pan

and anything, which was plenty, that the embodied mind of being there conjured up for the hour or so that we basked in this and our singularity, and in our commonality of sharing this place and our lives.

and anything, which was plenty, that the embodied mind of being there conjured up for the hour or so that we basked in this and our singularity, and in our commonality of sharing this place and our lives.

![IMG_6544[15644]](https://coordinatinggoldhagens.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/img_654415644.jpg?w=676) (Every guidebook will advise you to be prepared for these, and my experience on them was, I discovered, shared by all my fellow hikers. We all thought we were prepared. No one was prepared.)

(Every guidebook will advise you to be prepared for these, and my experience on them was, I discovered, shared by all my fellow hikers. We all thought we were prepared. No one was prepared.)![IMG_6539[15643]](https://coordinatinggoldhagens.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/img_653915643.jpg?w=676)

![IMG_6552[15646]](https://coordinatinggoldhagens.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/img_655215646.jpg?w=676)