We spent close to two weeks in Cape Town, said to us ahead of time by two reliable friends, to be a European rather than an African city.

My regard for them notwithstanding, I had my doubts that such a baldfaced statement might withstand the test of our exacting social scientific eyes. Boy, or — not to commit a micro-aggression — girl, was I wrong.

The Cape Town of our visit was overwhelmingly first-world and WHITE, and that’s because Cape Town might be fairly described as a post-apartheid city. That’s not to say that Blacks and Coloreds – these are standard apartheid legacy ways of categorizing people among all South Africans – aren’t in evidence. They are – often as waiters or clerks serving almost exclusively Whites. The continuing residential and spatial and wealth segregation of whites and non-whites, a de facto without being de jure apartheid, is manifest in a thousand different ways, which makes it impossible for a person not to be conscious (if at times only in the background of the mind) all the time. Whatever else it is, Cape Town can be conceived of as a soft-apartheid city. Massive townships, some with hundreds of thousands of residents and scant infrastructure and services, ranging from awful to dehumanizing, emanate far outwards from the city’s central, White core, or are sequestered off from the posh, gated and barbed wired, White suburbs.

The Cape Town townships – and therefore statistically Cape Town – constitute the most dangerous city in Africa. Gangsterism is a frequently heard term to characterize the quality and quantity of danger and violence of many of the area’s townships. Public transportation is appalling, creating effective commuting times of hours for many township residents to travel to their jobs (those who have them) in the central city. Cape Town, for all its fine features mainly for Whites, is sickening.

I can see how a (White) person with means, if willing to overlook or become inured to the larger degrading context and the human suffering it produces, could live well in Cape Town. Table Mountain (overrated as a natural and urban wonder, but nonetheless fine enough), great weather, inviting urban pockets, excellent restaurant, and perhaps enough cultural vibrancy, dirt-cheap cost of living (including wages for domestics), stunning beaches nearby and garden and wine country within an hour or two – it all adds up to a cushy and commodious existence. But the spiritual corrosiveness is unavoidable, whether one hardens one’s heart (QED: corroded) or not (it would eat away at you).

To be sure, I do not have the answers to the many questions of what to do and how to bring it about in a country of such massive economic (see Gini Coefficient), social (crime and violence rampant), health (HIV off the charts) spatial (de facto apartheid, built environmental disaster for most Blacks), racial (a country structured by race, racism, and racialism), and political pathologies (the government is massively and hopelessly corrupt). And it is easy for us to spend our three plus weeks in South Africa developing all our just criticisms while we enjoy the natural wonders, marvel with and at some of the wonderful people we meet, and viscerally experience the ordinary horrors that are the commonplaces of this country, and then to leave on our merry way, bequeathing little more than a few withering blog entries in our trail. So, we – Sarah, Gideon, and I – talk, and talk, and talk, and who knows what it will yield.

Among the wonderful people we have met, we spent several days in Port Elizabeth with Kevin Kimwelle, a personally winning and professionally admirable architect and social activist, with whom we will surely keep in touch (and about whom we, probably Sarah, will write more).

Mark Coetzee (see https://www.conceptualfinearts.com/cfa/2017/06/30/mark-coetzee-interview/), the director of the just-to-be-opened Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art, hugely impressive and thoughtful, spent a couple of hours with us, touring the museum and explaining to us the building process and choices – of mission, art, staff, and institution – in a society characterized and riven by all the features (and more, such as violent homophobia) I have mentioned.

We learned a great deal from Mark in a short time, and even received a fairly spirited critique of our, in his view, blinkered critique of South Africa – though it was unpersuasive as the defense mainly took the form of pointing to the inequalities and horrors of other countries (real or exaggerated). Lest I leave the wrong impression, Mark told us that he had been a long-time anti-apartheid activist who had to flee the country in the 1980s, that he decries the ongoing soft-apartheidism of South Africa, and that he works to privilege and give voice to African artists (mostly non-White), and to create as progressive an institution as possible. It may be more complicated than Mark’s self-representations (how would we know?), as he, a self-proclaimed Marxist, comfortably and successfully works at the highest and wealthiest echelons of the notoriously non-Marxist art world, which suggests that he may be caught in what the Marxists call a contradictory position, one of less than full self- or self-representational enlightenment. In any case, for us, Mark, memorable as he is, will just be a memory.

In the Drakensberg, we met, climbed with, and broke bread with a range of people, mainly Europeans, who gave further support to the well-established notion that people who appreciate nature enough to want to hike along or up it are generally nice people, or at least they bring their better selves on these adventures. Of particular note, aside from the always helpful and earnest South African staff of the lodge, were two Germans who were more or less permanently in Southern Africa to bring the word of their God to others. They were full of the well-meaning passion which I have encountered in Jehovah’s Witnesses, which they were. Miriam and Mike have devoted themselves to living by their humanistic (if godly inspired) principles, going door to door giving witness and spreading their enlightenment. Even though their understanding of godly issues is decidedly not mine, I like such non-self-righteous-righteousness, and admire those who espouse and practice such an orientation’s maxims. Salt of the earth was coined to describe such people. Their optimism and positive spirits are infectious. We shared a couple of lovely meals and a bunch of laughs with Miriam and Mike. Who knows if we will ever be in touch with them again. If we do, I will be happy.

There were, of course, all the many South Africans of whatever skin color (race) and station we encountered. All-in-all, nearly without exception (except for a few race-coding Whites), people were lovely and kind, with smiles all around (except from the flow of beggars). We talked to as many people as we could, mainly Blacks and Coloreds, with the passing questions and conversations that can come with such chance and fleeting encounters. Our impressions of those we encountered is that the people were well-educated and thoughtful, with much human capital and ambition, and therefore ready to take off if economic and professional opportunity were to come their way. From our end, all we had to do (we usually offered more) is mention New York, which has cache with everyone.

The densest and most significant contact we had with South Africans was orchestrated by Gideon, who in his by now typical manner, went about on his own, and met a group of Black (perhaps some designated as Colored) young men and women, who integrated him into their squad (he immediately was let into their group chat) and with whom he ran day after day and became friends, real genuine friends. They met over a rap song in McDonalds (Gideon was rapping along, the others, sitting nearby, laughed, and they all started talking), and the rest is history. They – Larnelle, Clyde, Llewyn, Judah, Henry, and Octavia – poor enough that on the last day we were there, they didn’t have enough money to come into Cape Town. Sarah and I suggested that Gideon offer to pay for their transportation and food, which he did. They accepted eagerly, saying in the seemingly ubiquitous youth vernacular we there, and had a wonderful day together. Though for Gideon, the time with the squad was mainly sweet — as he really liked them, they had great and memorable times together, and his friends showed him their Cape Town and their humanity – it was also bitter.

As Gideon was acutely aware, compared to them, he is a billionaire. While after a day with the squad, he returns to the perfectly nice apartment we rented, they have to somehow get back (or walk the streets at night—no joke) to their townships about which Octavia, upon saying goodbye to Gideon one day, said, now we go back to hell. And of course, all the fellow-feeling notwithstanding, Gideon and we resume our privileged trip-around-the-world and then our privileged life in New York, while they, his good friends, just because they were born with darker skin in this apartheid structured country, will try to overcome (with what success? and what will failure mean?) the seemingly multiple insurmountable hurdles which may auger a life of privation and suffering.

When it was time the last evening for Gideon to take his final leave, Larnelle and Clyde accompanied Gideon to our apartment building. I went down to the street to let Gideon in, and got to greet them. Big smiles, sweet faces, vigorous handshakes, words of thanks to me for letting them meet and spend time with such a great kid as Gideon. With equal enthusiasm and gratitude, I thanked and complimented them in turn for their kindness and generosity towards him, before the farewell hugs warmed and broke my heart, and more so Gideon’s. Gideon fears he may never see them again, though social media (Gideon has friends all over the word) will keep them in touch.

The whole situation, and especially the contexts of the lives of Gideon’s friends, breaks my heart. It breaks Sarah’s. Most of all it breaks Gideon’s.

— Danny

![IMG_6544[15644]](https://coordinatinggoldhagens.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/img_654415644.jpg?w=676) (Every guidebook will advise you to be prepared for these, and my experience on them was, I discovered, shared by all my fellow hikers. We all thought we were prepared. No one was prepared.)

(Every guidebook will advise you to be prepared for these, and my experience on them was, I discovered, shared by all my fellow hikers. We all thought we were prepared. No one was prepared.)![IMG_6539[15643]](https://coordinatinggoldhagens.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/img_653915643.jpg?w=676)

![IMG_6552[15646]](https://coordinatinggoldhagens.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/img_655215646.jpg?w=676)

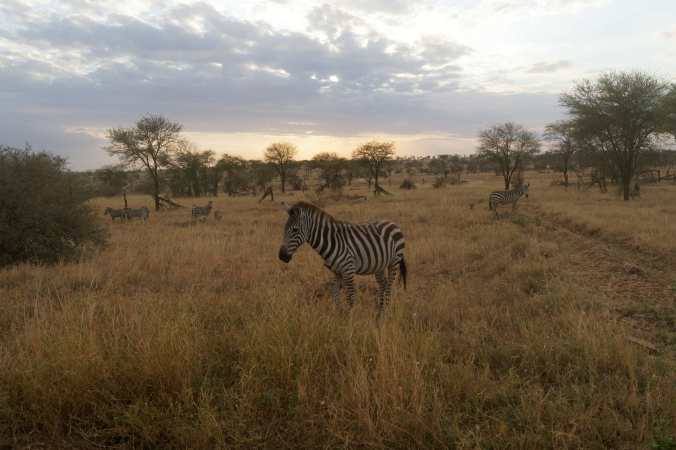

My thoughts and feelings about seeing the animals, the raison d’etre for safari, is different in character and more mixed – not nearly as plural yet more valent than my reactions to the landscape. As I have already indicated with my semi-joking characterization of some of the major players — zebras and gazelles grazing, hippos lazing, giraffes raising, water buffaloes gazing, elephants amazing – the animals are spectacular to see and to see in their world, as opposed to the artificial worlds we create for them in the US and elsewhere. Being up close to them in nature speaks for itself as a singular way to experience them.

My thoughts and feelings about seeing the animals, the raison d’etre for safari, is different in character and more mixed – not nearly as plural yet more valent than my reactions to the landscape. As I have already indicated with my semi-joking characterization of some of the major players — zebras and gazelles grazing, hippos lazing, giraffes raising, water buffaloes gazing, elephants amazing – the animals are spectacular to see and to see in their world, as opposed to the artificial worlds we create for them in the US and elsewhere. Being up close to them in nature speaks for itself as a singular way to experience them.

We, in rolling fortresses, encountering again and again others in their rolling fortresses, with two or five or ten or more of them repeatedly convening, cameras pointing and clicking, at the site of a notable animal sighting. (This occurs because the guides, who know each other and work collaboratively, are in constant touch with one another about the animals.)

We, in rolling fortresses, encountering again and again others in their rolling fortresses, with two or five or ten or more of them repeatedly convening, cameras pointing and clicking, at the site of a notable animal sighting. (This occurs because the guides, who know each other and work collaboratively, are in constant touch with one another about the animals.)